Bloggers Jane Davidson and Nick Marsh team up to consider how much of each task on a typical invoice for surgery would, and could, be undertaken by a VN or vet. It reveals how, despite its importance, the role of the VN goes unnoticed and unrecognised.

When Jane suggested writing a blog together, I thought it was an excellent idea. When she suggested it to our editor, he was struck with a vision of us singing a duet of You’re the One That I Want – and we couldn’t get much sense out of him after that.

When Jane suggested writing a blog together, I thought it was an excellent idea. When she suggested it to our editor, he was struck with a vision of us singing a duet of You’re the One That I Want – and we couldn’t get much sense out of him after that.

Nevertheless, the more I thought about it, the more I liked it (the blog, not the duet) – nurses and vets are not islands within a practice; the successful outcome of many patients depends on their teamwork.

But how much of this, Jane wondered, is visible to the client?

I’ve been researching some information on uniforms for vet nurses. This may seem a little off-piste, but there is a purpose. Bear with…

I’ve been researching some information on uniforms for vet nurses. This may seem a little off-piste, but there is a purpose. Bear with…

It started as looking at the issues with hygiene and infection control, and has, so far, resulted in an article with The Veterinary Nurse. While researching for this, I found information about the identity – or lack of – we have as vet nurses.

This got me thinking. A number of issues exist in the vet nursing industry. We have VN Futures working to address many of these, but I’ve looked at a lot of the actions and have boiled down our issue to something basic and simple – in many senses, we are invisible.

Our uniforms don’t always mark us as different to other staff, so we are lost visually. We are lost financially, as our skills are rarely invoiced as RVN skills on veterinary invoices. The income we generate is rarely apportioned to us.

This has been an issue for me personally and I’ve heard other nurses in situations where they have been told to increase the fees they make. But if we are not fairly being represented for what we do already, how can we increase that?

Understanding contribution

Our skills are not just about nurse clinics and selling food, but how can we get clients to suddenly start paying for nurse clinics if they have never seen a payment for any nursing skills before?

Our skills are not just about nurse clinics and selling food, but how can we get clients to suddenly start paying for nurse clinics if they have never seen a payment for any nursing skills before?

This may sound like a small thing, but if our employers cannot invoice for our time and skills, how do they know how much we bring into the practice? How can a vet practice, as a business, run without knowing who does what and how much it costs?

If clients cannot see where we have helped in their pets care via an invoice, how are they to understand what our contribution is? We know people don’t always value things they get for free, so where is our financial identity when we are seen as a “free” commodity?

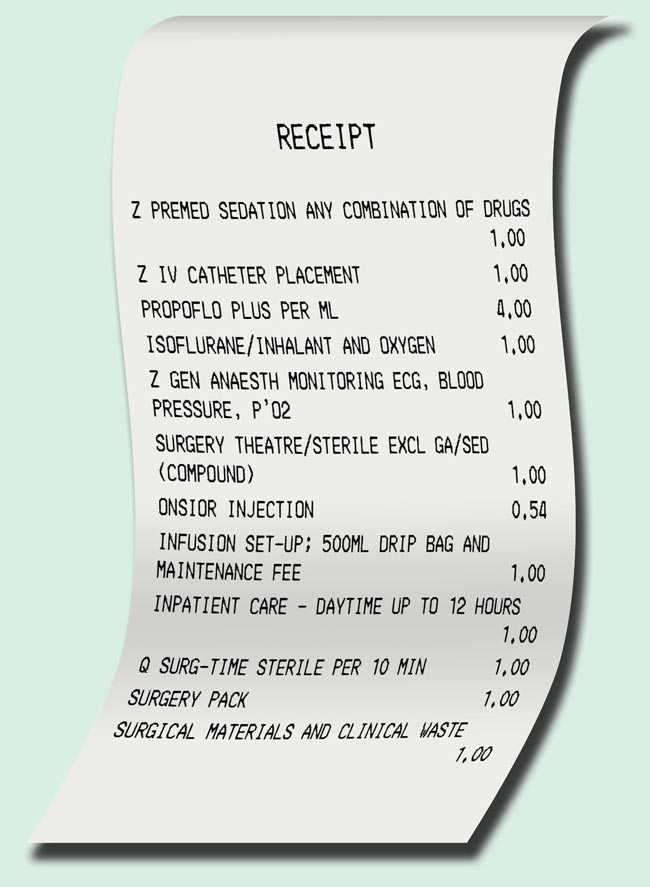

I’m starting this journey with this blog and by looking at a typical vet invoice for surgery. Nick and I looked at this invoice (right) separately. It’s a real invoice, for surgery on one of my pets. The fees have been removed, and Nick and I have decided how much of each task would, and could, be undertaken by a VN or vet.

We both have a lot of experience, so I’m hoping we give a balanced view.

Nick’s invoice view

General anaesthetic and monitoring

I have enormous respect for nurses performing the bulk of anaesthetics in general practice (referral and specialist practices usually have specialist anaesthetists and anaesthetic nurses, as with human medicine). When I was a student on my anaesthesia rotation, I found it alternately incredibly dull and stressful.

When everything is stable; monitoring heart rates, jaw tone, mucous membrane colour, oxygen and carbon dioxide saturations can be tedious, but it can become terrifying at any second. I spent most of my rotation thinking “should I tell the surgeon the heart rate has gone up 10 beats? Is that significant? They look very cross. I really don’t want to annoy them”.

Anaesthesia is critical, of course, and a massive part of the job, and the responsibility is placed on the nurse. Generally, the vet chooses the protocol and the nurse puts it into practice.

In a good team, both vets and nurses contribute to both the protocol and the monitoring of it, but it’s the vet’s name on the bill.

Premed sedation

Similarly, the usual situation for premedication is the vet decides on the protocol, while the nurse administers it. But, in a good team, the nurse will alert the vet to any conditions they may have overlooked in deciding their protocol (which is a quaint euphemism for “forgotten about between consults”).

Catheter placement

Who does this varies from practice to practice. In some practices, the nurses immediately place IV catheters on admission, in others the vet does it around the time of premedication. However, you’re unlikely to be able to work it out from the invoice.

Propoflo/isoflurane inhalant

Both part of the general anaesthetic, but it’s almost certainly a nurse that topped up the vaporiser in the morning and drew up the anaesthetic ready for administration.

Surgery theatre/sterile

Now, the vet obviously plays a major role in the surgery. It is, after all, the fun bit, as well as the messy bit – and there’s no way you’re going to stop vets being involved in things that are both fun and messy.

Now, the vet obviously plays a major role in the surgery. It is, after all, the fun bit, as well as the messy bit – and there’s no way you’re going to stop vets being involved in things that are both fun and messy.

Surgery is frequently complicated and often stressful. A horrible, sinking feeling occurs that only someone in sterile scrubs, with their hand inside another living being, ever knows – I call it the “surgeon sweats”. It’s the feeling the operation is not going according to plan, that it’s very hard to see the end, and you suddenly want more than anything to be able to scratch your nose, sit down and think. The friendly face of a nurse can be invaluable here.

Nurses are emphatically not just for moral support. They are the reason the theatre (and the vet) are sterile in the first place and they are the ones who will be cleaning up any mess left behind, as well as cleaning the instruments (and, as is usual in my case, cursing the vet for once again forgetting to remove the scalpel blade from the blade holder, but consoling themselves that, once again, the vet will be buying doughnuts in penance).

They are responsible for preparing the patient and for sitting with it while it recovers, as well as a myriad other tasks that I probably have forgotten because I’m not the one who has to do them.

Infusion set-up

No prizes for guessing who did the setting-up.

Inpatient care

It’s not often I feel jealous of nurses in practice. They have a hard job, with a lot of responsibilities, and their pay – for all their training – is shamefully low. However, when I’m running between consults and phone calls, and prescriptions, I see nurses spending time with the patients.

I know they’re not just sitting and cuddling them, they are monitoring and checking, and injecting and cleaning, but they are actually spending time with the animals – and I get a twinge of jealously general practice doesn’t have more moments like that for the vets, too.

Surgery pack/materials and clinical waste

Packed, cleaned and disposed of by the nurse, of course.

Histological pathology examination

Ah, the remit of the pathologist, universally acknowledged as the most dashing, daring and “gosh-darn-it-all” sexiest members of the veterinary profession (I did mention I’m a resident in clinical pathology, didn’t I?).

Jane’s invoice view

I asked permission from the practice that generated this invoice to share it. The vet told me the anaesthesia monitoring item is intended as a nursing task, but, in clarifying, said the fees go to the person who prices it up, not the nursing team. The vet has said the practice will now specify this is a nursing role on future invoices, so it is clear to the clients. Great news!

I asked permission from the practice that generated this invoice to share it. The vet told me the anaesthesia monitoring item is intended as a nursing task, but, in clarifying, said the fees go to the person who prices it up, not the nursing team. The vet has said the practice will now specify this is a nursing role on future invoices, so it is clear to the clients. Great news!

But we need more.

Inpatient care is likely to be heavily nurse-based, so why not say it? Why aren’t nurses pricing up for the skills they have carried out? I know some practices do this, but not all, and certainly not enough practices have this recognition of nursing skills.

My experience is the fluid set-up, IV placement and maintenance of fluids will be a mainly nurse-centred role in many practices – as with administering a premedication or postoperative medication, preparing kits, and removing and administration of regulated waste.

In agreement

Nick has agreed with me all the way through, with the only difference being I apportioned all the surgical fees to the vet – Nick correctly pointed out the reason the theatre is ready to use is a nursing role. Thanks, Nick!

This leaves an equal invoice in terms of fees generated. I have the fees and can say if we apportion tasks to nurses/vets/jointly then the income from the bill is split almost evenly between the vet and vet nursing teams. It does make me wonder the age-old question – do we charge appropriately for our time?

Why is this an issue?

As aforementioned, it makes us invisible. To the business, the client – even ourselves.

I believe it has an impact on several issues. I have found vets are much more able to return to work after maternity leave. Is this because practices can see their financial worth, in terms of fees, and work out how much they will earn in their part-time hours? Are nurses, who rarely have this financial standing in practice, and as part-time, seen as a burden of cost for less work?

Having seen the fee breakdown of vets, it is clear surgical vets will usually be the top fee earners per hour due to the differing nature of treating medical and surgical cases.

If no scale of fees exists for our skills, how easy is it to decide what skills to learn and improve to advance our careers? While some practices pay more for further qualifications, it seems to be given whether you use your new skills or not. So, perhaps an incentive for using these skills and improving patient care would make vet nurses more motivated to undertake advanced and structured CPD. This will then reflect on career progression – something many vet nurses feel they don’t have access to.

While we do learn more and advance our skills, formally and informally, it is hard to chart our progress. This seems, to me, to be because we do not always get to write up our cases and patient notes, or apply fees to our new skills. We often rely on other people’s perceptions of our skills and our role in a team, rather than hard evidence of what we have done.

Final word

Sitting down and taking the invoice to pieces like this, as Jane suggested, it’s striking how many of these tasks could not be done without the veterinary nurse – or, at least, would take much longer and be performed much less effectively.

Sitting down and taking the invoice to pieces like this, as Jane suggested, it’s striking how many of these tasks could not be done without the veterinary nurse – or, at least, would take much longer and be performed much less effectively.

I don’t say this to downgrade vets – heaven knows, it’s a stressful enough job, and the ultimate responsibility for the case rests with them – but seeing an invoice go out with the vet’s name next to every one of these items is further evidence nurses have a long way to go to achieve the recognition they truly deserve; recognition for their training, knowledge, support and indispensability in the veterinary world.

I took this joint work very seriously and, so, in recognition of the nature of the relationship between vets and nurses, I submitted this copy to Jane far too late and left her to do most of the work.

Nevertheless, it’s been great fun working with her for the blog. Which reminds me – I wonder if there’s a good karaoke bar close to BSAVA Congress?

Leave a Reply