Since starting a career in clinical pathology, I have seen a lot of strange and wonderful sights down my microscope…

It’s like being given a window into weird new worlds – tiny battlegrounds of leukocytes, tumour cells and microorganisms, against a backdrop of cytokines, stroma and necrosis. It’s not quite Saving Private Ryan, but with a little imagination and knowledge, it can be fascinating.

We’re humans, though, and we’re very good at turning the fantastic into the mundane, particularly when we’ve got a large stack of other battlegrounds to look at before we’re allowed to go home.

Cytology nerds

However, one thing I’ve discovered is that, for the most part, pathologists are fundamentally nerdy (although, weirdly, none of the others can recite the sadly missed Rutger Hauer’s “tears in rain” speech from Blade Runner off by heart, or Quint’s “Indianapolis” monologue from Jaws), which means many of us have our favourite cells – creatures that we rarely tire of seeing, no matter how late the hour.

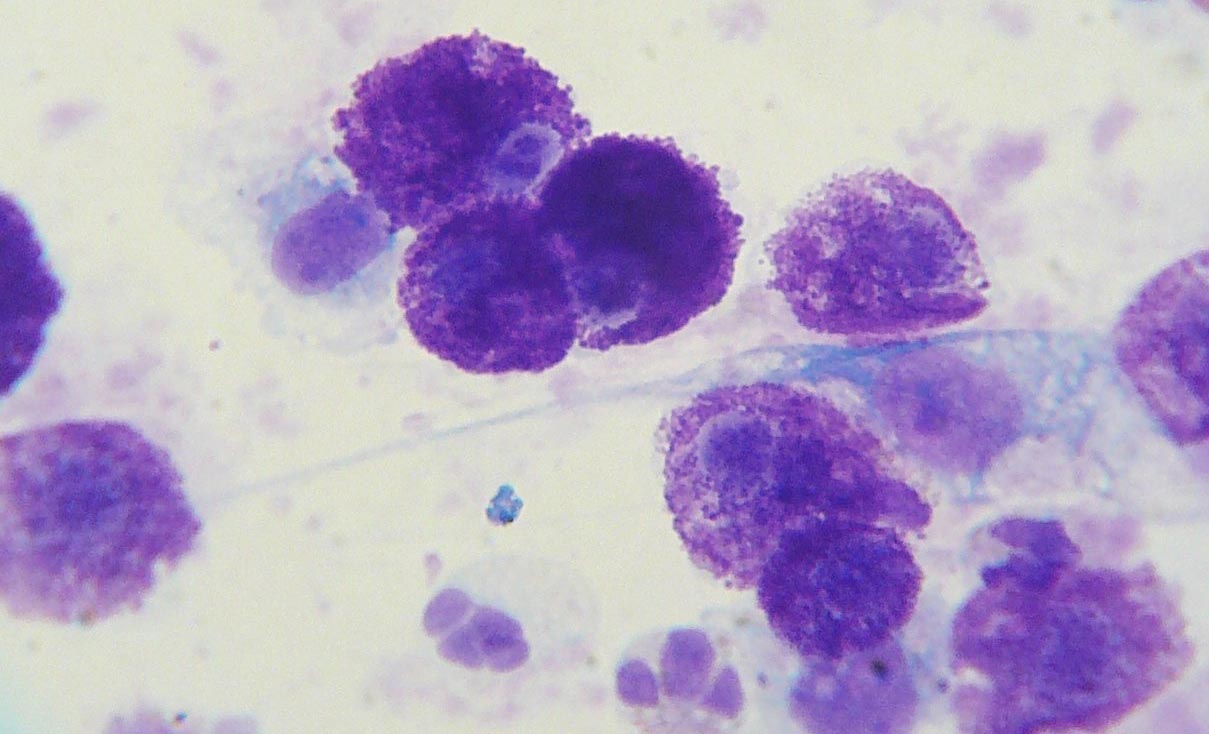

For a lot of them, mast cells hold a particular beauty, and I can understand that.

They’re round cells chock full of deep purple granules, eye-catching and unique, and purple always was my favourite colour… but they’re not for me.

See, those granules are full of cytokines, chemical harbingers of inflammation, and although they’re a vital part of the immune system, when they go wrong, mast cell tumours are intensely itchy – painfully so – and occasionally extremely aggressive. This means when I spy them down my ‘scope, they look spiky to me, buzzing like tiny bees with their payload of pain (I mentioned the imagination bit earlier, didn’t I?). It takes the edge off their beauty.

Nick’s No. 1

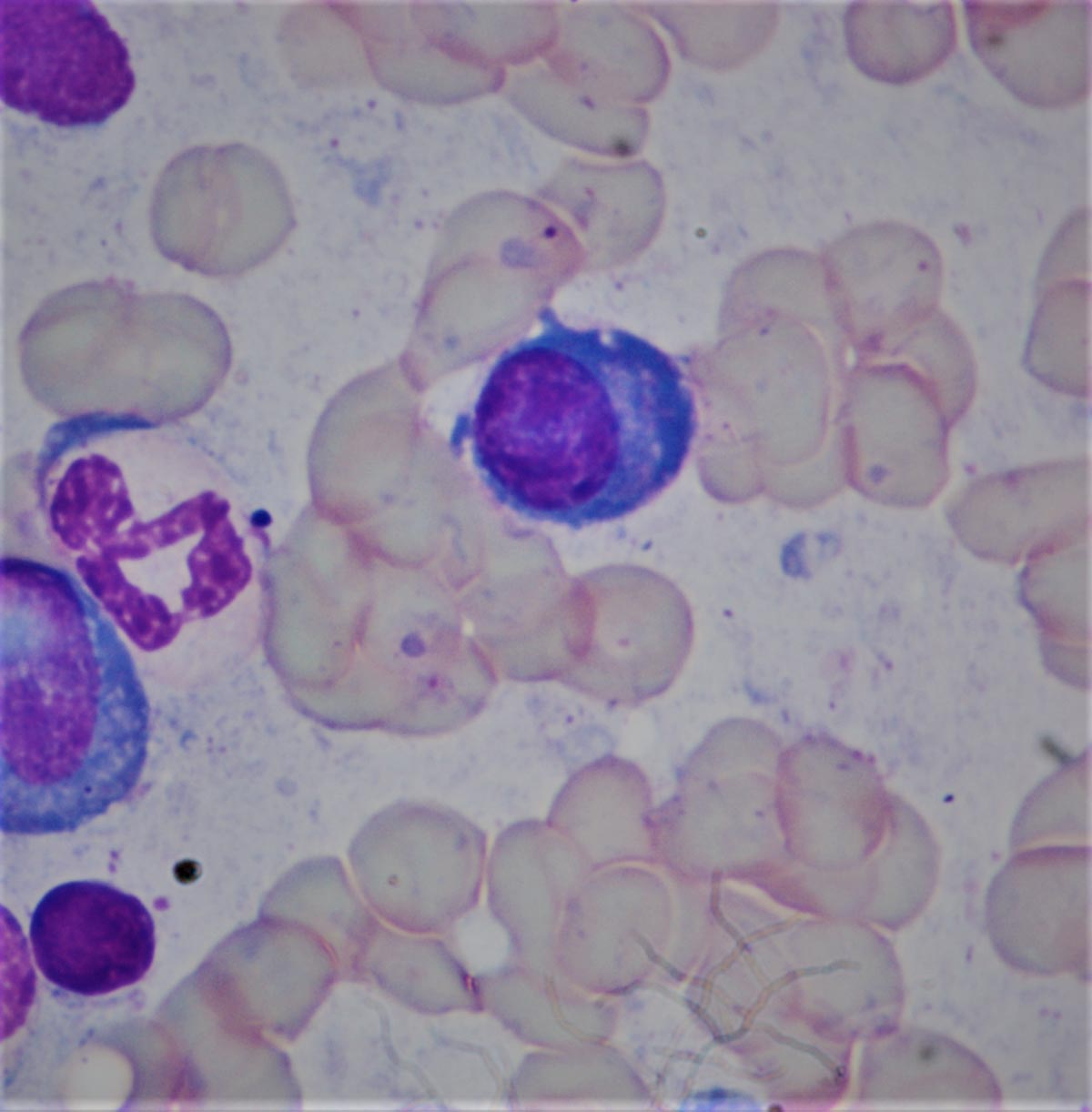

I have my own favourite – my particular pathological paramour is the regal plasma cell (below). Take a look at it. Is that not a thing of beauty?

Look at that gorgeous nucleus – round, purple, and cracked, like an African river bed waiting for the summer rain.

How about that deep royal blue cytoplasm? Or the clear area just next to the nucleus? If only Da Vinci had a decent microscope, the Louvre would be packed with people gazing at one of these beauties instead of a “slightly constipated Florentine woman”.

I sense I’m not winning you over – if not, let me tell you why they look like they do…

A day in the life

Plasma cells start life as a B-lymphocyte, and it is one of the lucky few lymphocytes whose unique receptor has found the antigen it has been waiting for – the one tiny fragment of material amongst the millions of possible tiny fragments that fits the receptor like a key in a lock, and has stimulated that cell to change and progress.

The B-lymphocyte becomes a munitions factory, giving over all its cellular machinery to making antibodies, all targeted against the antibody that triggered the process in the first place. That cracked nucleus is a hive of DNA transcription, and the clear area next to the nucleus is the Golgi apparatus – a cell-sized protein foundry, visible via the microscope, pumping out antibody after antibody, all packed into that wonderful deep blue cytoplasm until they’re released to help with the fight.

When cells (don’t) attack

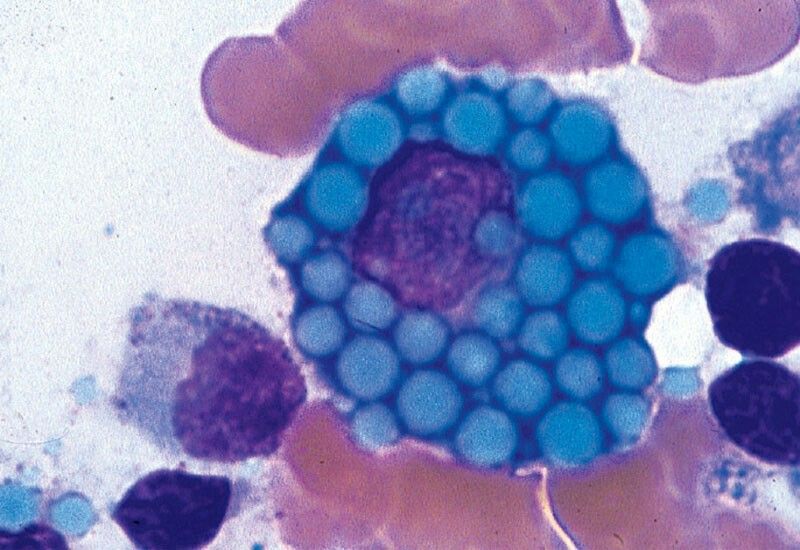

Even when they go slightly awry, plasma cells are pretty – look at this:

This is a constipated plasma cell (a Mott cell). Those blue packets inside it are jammed up with antibodies the cell is failing to release. You don’t just find them in circles, either – I’ve seen Mott cells jammed with needle-like structures, and even tiny geometrically perfect triangles, all full of ammunition.

Add to all this wonder, the name of the cells – “plasma cell” – puts me in mind of space opera science fiction (rebels fighting evil empires, laser cannons and planets exploding)… basically it hits me in my happy place.

A very naughty boy

Now, I was rather down on mast cells because of how they behave when they’re being naughty. But what about plasma cells?

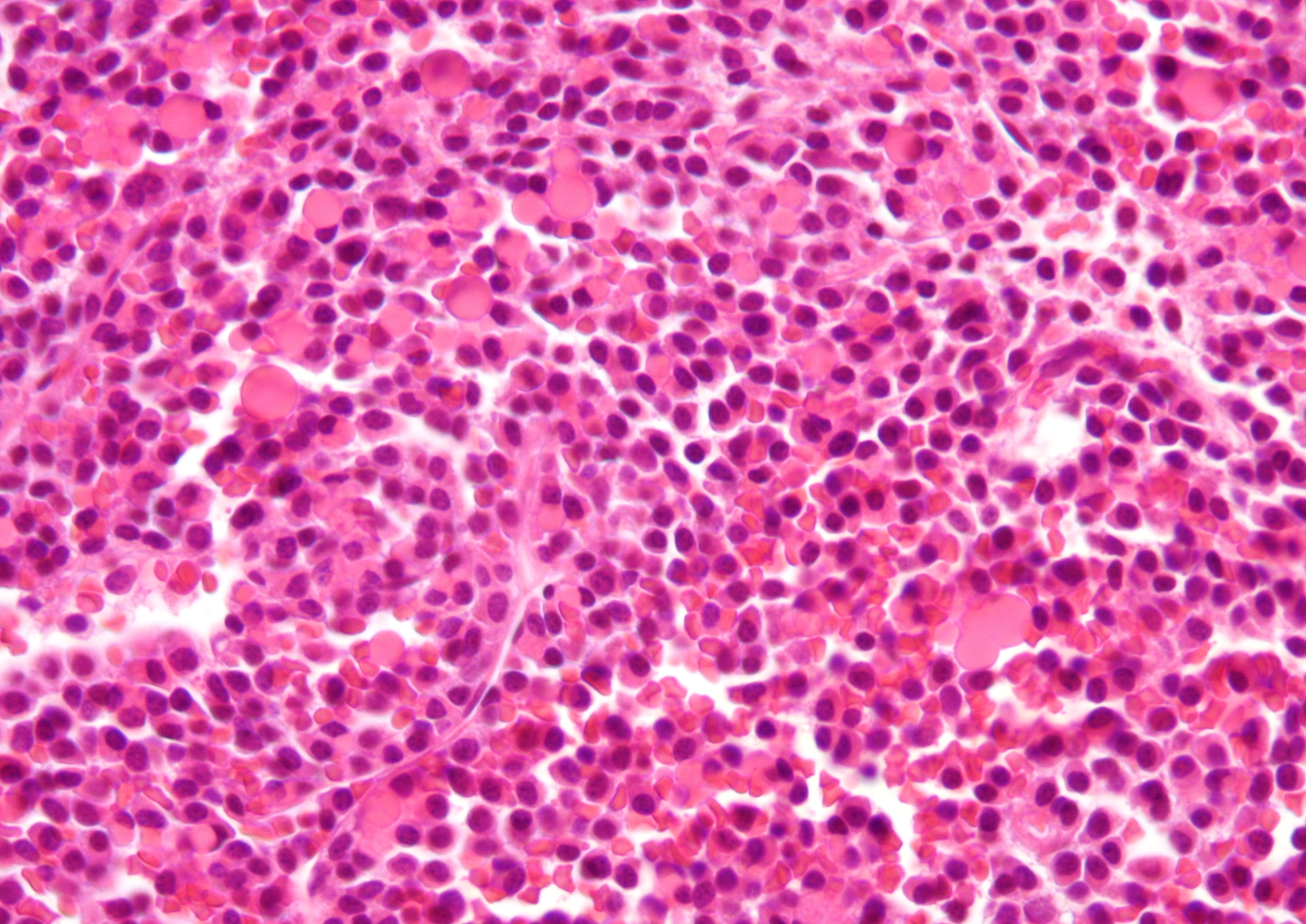

Well, unfortunately, the very naughtiest plasma cells are very naughty indeed – they’re the cause of multiple myeloma, an extremely serious and hard to treat form of leukaemia, filling up the bone marrow with plasma cells that no longer listen to the checks and balances that try to stop cells doing exactly whatever they want.

But myelomas are relatively rare, at least in the patients I deal with. Far more commonly, we see plasmacytomas – these are usually benign cutaneous masses, which cause serious complications only rarely and are, honestly, so wondrous to behold on a glass slide that, had van Gogh been able to look at one in his lifetime, he might have given us more than sunflowers to think about.

Leave a Reply