I’ve talked about “The Big C” before, and how “cancer” – despite the fear the word induces – is a broad term for a wide variety of diseases that share a similar cause (uncontrolled cell division). As descriptive terms go, it’s not much more specific than “virus”.

Today, I’d like to dig into that a little more…

I spend much of my day job classifying lumps and bumps into one category or another – classifying a tumour predicts its likely behaviour. One day soon, it won’t really matter what classification a tumour fits into; the days of “tumour agnosticism” are dawning, when what will really matter is a tumour’s genome and its surface markers, so that drugs and therapies can be specifically tailored to them. Until then, I’ll continue to look down microscopes and report what I see.

Pathologists like myself classify tumours into three broad categories – based partially on the cells they’re derived from and partially how they appear down the microscope.

Epithelial neoplasia

Epithelial cells are derived from the embryological ectoderm – well, they are for the purposes of pathologists. For everyone else, they come from all embryological layers (look, it wouldn’t be proper science if we all agreed on everything, would it?) – and the thing to remember about them is that they are very, very good friends.

I’m sticking with you

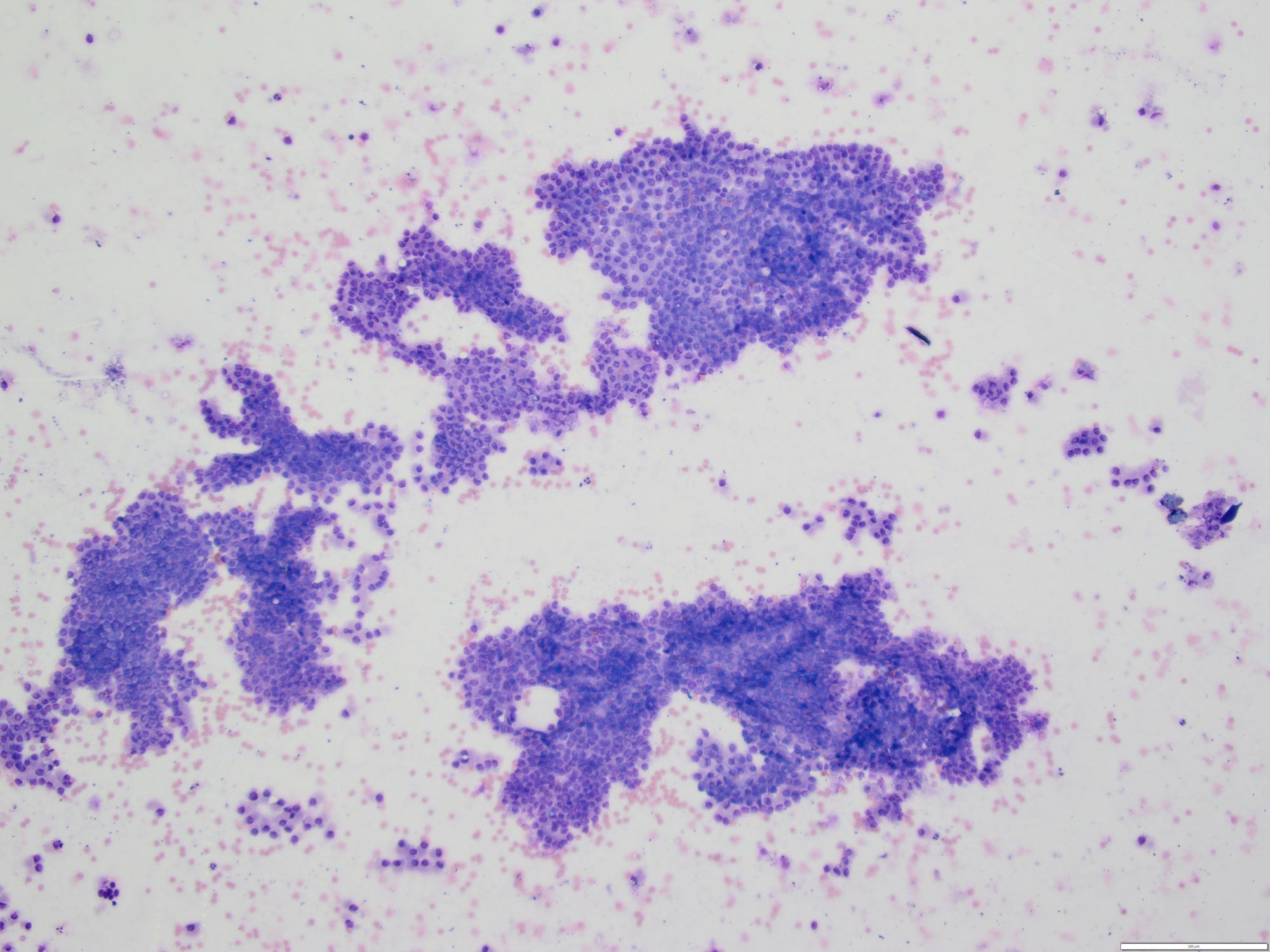

Epithelial cells love each other and cling to each other very tightly; their cell to cell junctions are the strongest of all the cell types, which means when someone is cruel enough to stick a needle into a piece of tissue and suck them out to splat them on to a slide so I can have a look at them, they often bring a lot of their friends along with them.

Due to their tightly cohesive nature, we describe groups of epithelial cells as “clusters”, and they are the best at forming patterns on the slides I look at. We describe such patterns as “pallisading”, “trabecular”, “tesselating” and other exciting if largely meaningless words to general practitioners.

The point is epithelial cells often manage to retain at least some of their original architecture (their relationship to each other) by the time I get to see them, which helps me to identify the type of tissue they may have arisen from.

Ex-best friends

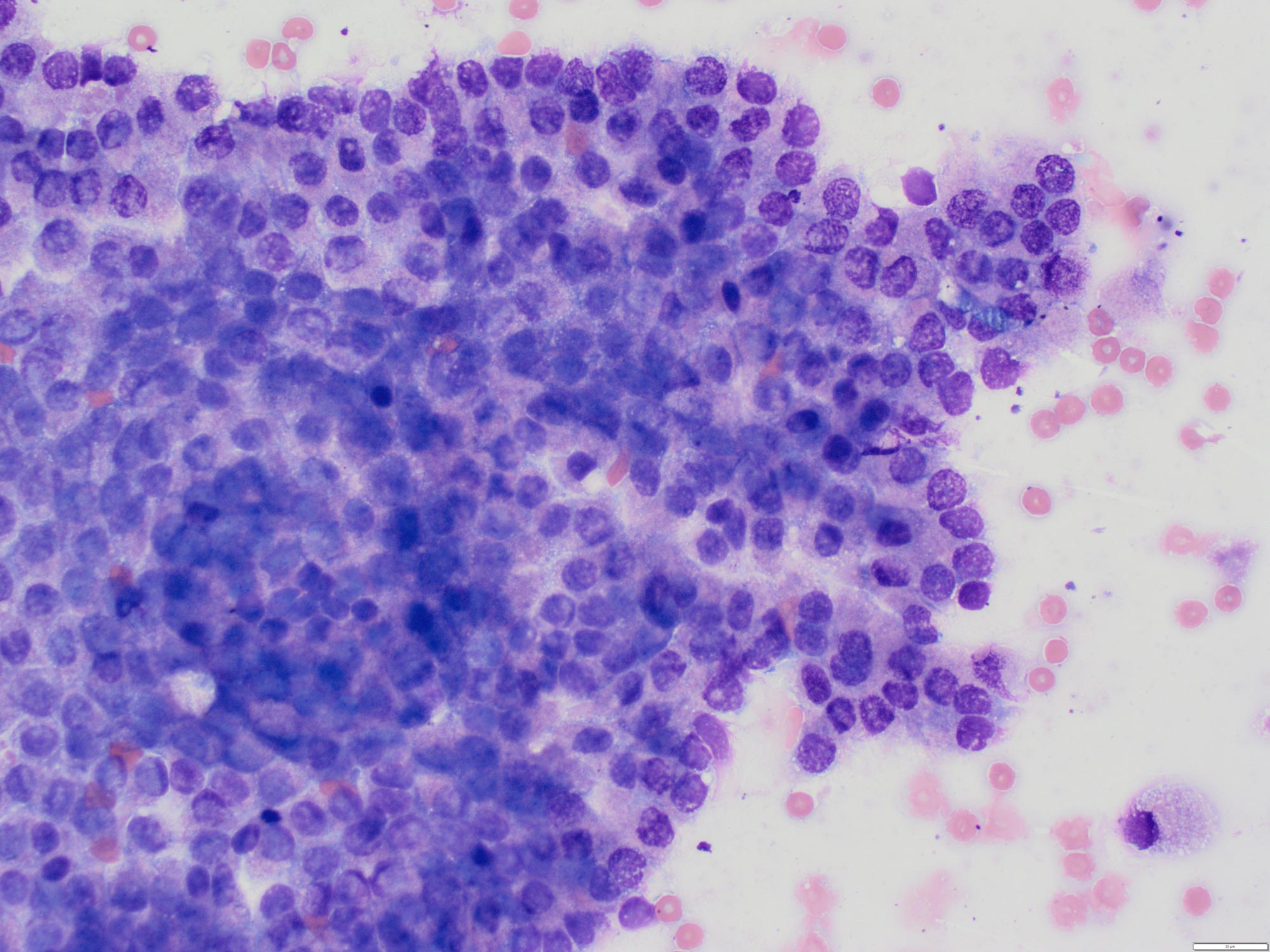

The fly in the ointment is that, to break away from their original tissue, nastier epithelial tumours have to give up their friendships – they become less cohesive, and resemble their neighbours less and less.

Highly malignant epithelial cancer mutates a long way from the original tissue, and these cancers tend to form much looser clusters and lose their pattern, making their origin hard to identify on cytology slides.

Adenomas and carcinomas

Tumour names generally reflect their classification. Benign epithelial tumours are often described as “adenomas”, and malignant epithelial cancers are usually called “carcinomas”.

As well as giving a clue to their origin, the name gives an indication of their behaviour – carcinomas are often likely to metastasize, and when they do, they usually spread through the lymphatic system; epithelial cells have no earthly business within a lymph node, and when they are found there, they are often a sign of metastatic disease.

Mesenchymal neoplasia

Mesenchymal cells (or as my dictation software usually insists on describing them, despite a great deal of training to the contrary, “was in Kabul” cells) derive from the embryological mesoderm and form the connective tissue of the body – fibrous tissue, fat, scar tissue, bone.

They are also rather Lovecraftian, in that their behaviour is all about extending tendrils and insidious invasion.

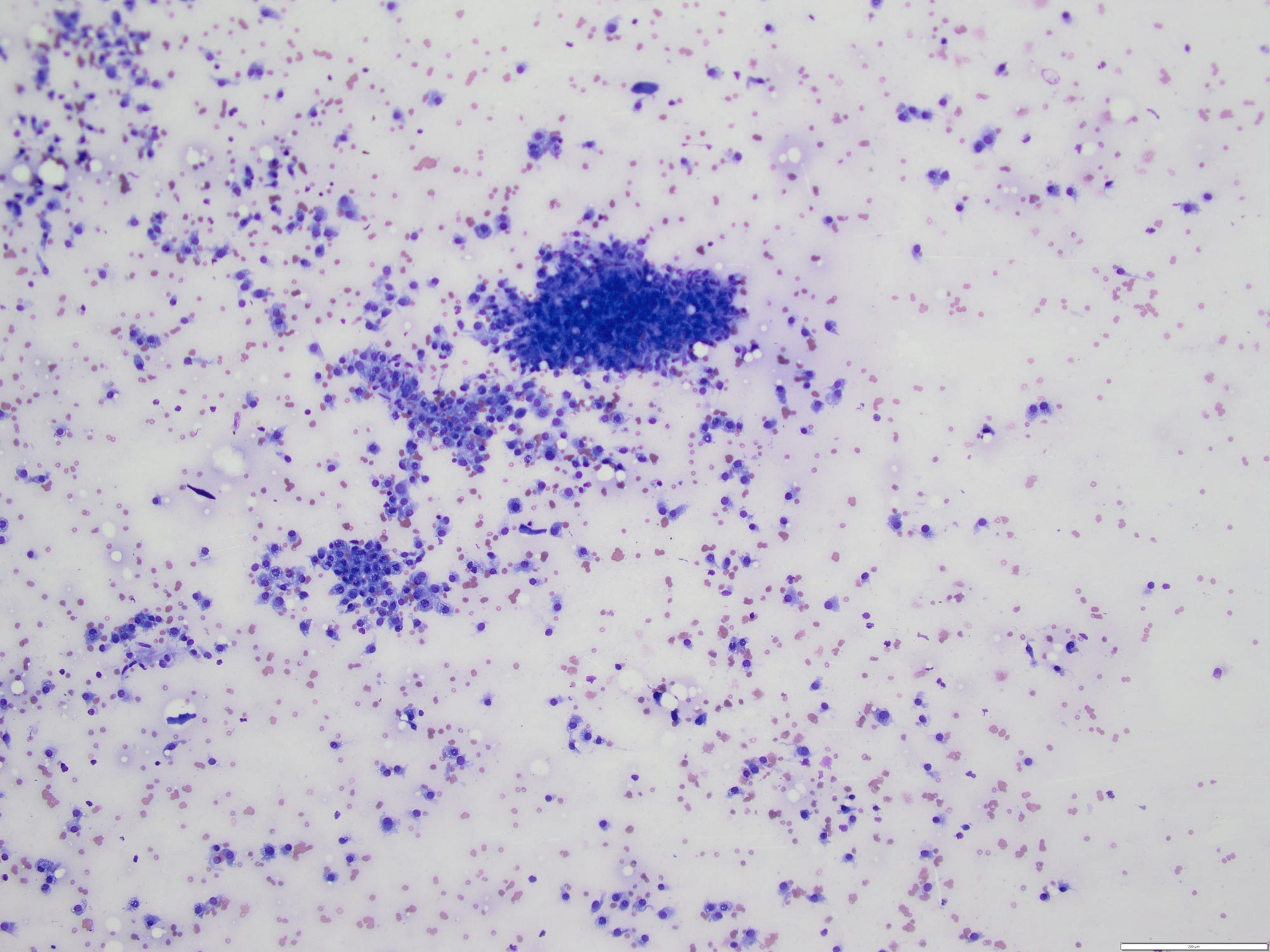

Despite the “connective”, these cells are less good friends than epithelial cells, and on aspirates they form looser “aggregates“, and are often found as individual cells.

Insidious

Benign mesenchymal tumours include lipomas, fibromas and the like, whereas malignant tumours are given the more specific name of “sarcoma”. Sarcomas, for the most part, behave in a similar fashion – they slither into local tissues, invading them.

Metastasis is less common in sarcomas, but when they do it, they usually do it in the blood vessels, largely by poking their tendrils right through the vessel walls. The tips of the tendrils break off and embed themselves at another location, where they cling like a limpet and extend their tendrils all over again (told you they were Lovecraftian).

Sarcomas are perhaps most deserving of the term “cancer”, derived from the Latin word for “crab”, because once they’re attached they’re absolute buggers to pull off.

‘Round cell’ neoplasia

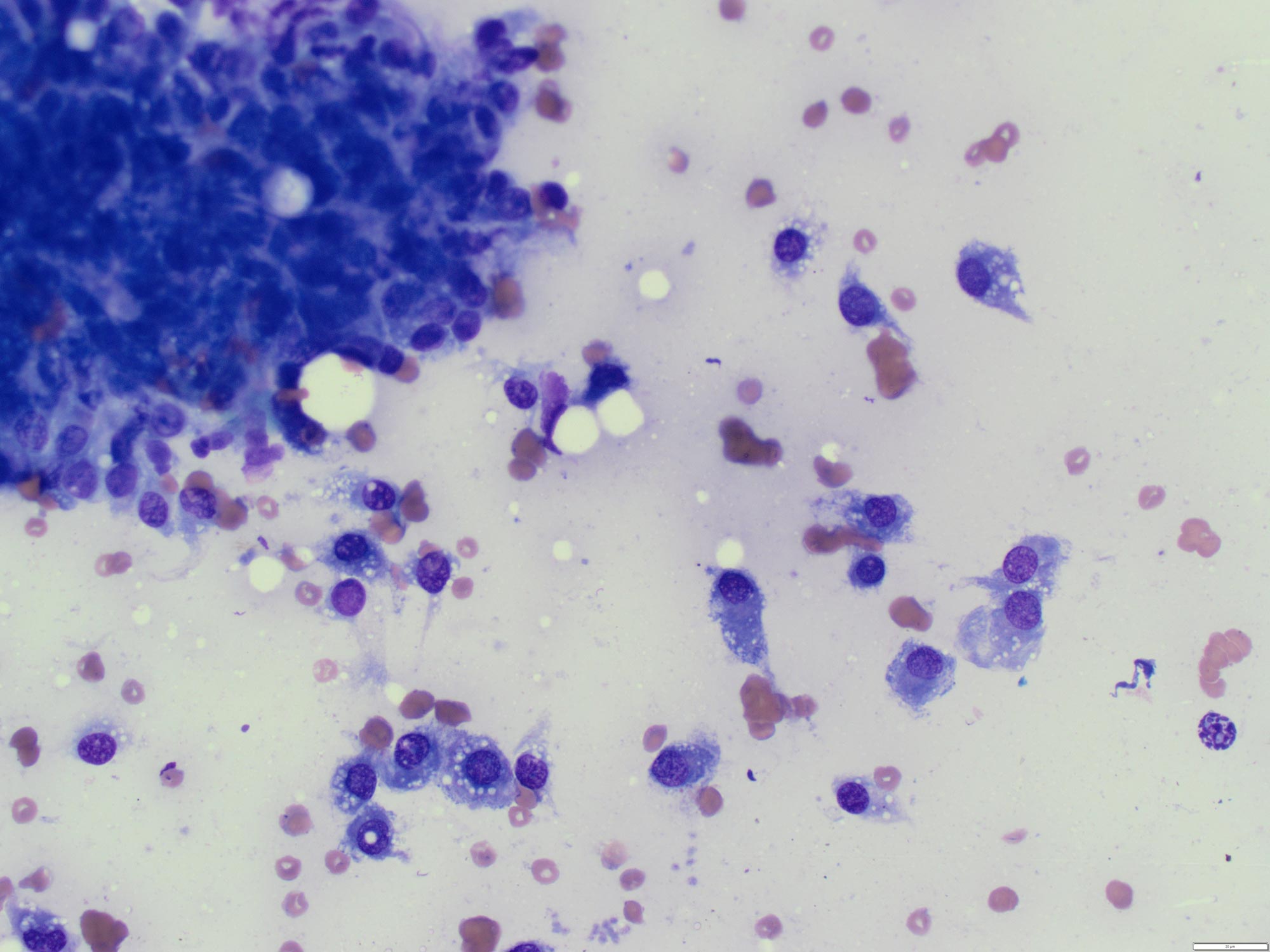

Rather less satisfyingly than the other categories, round cell tumours are so described because they are… well, made of round cells.

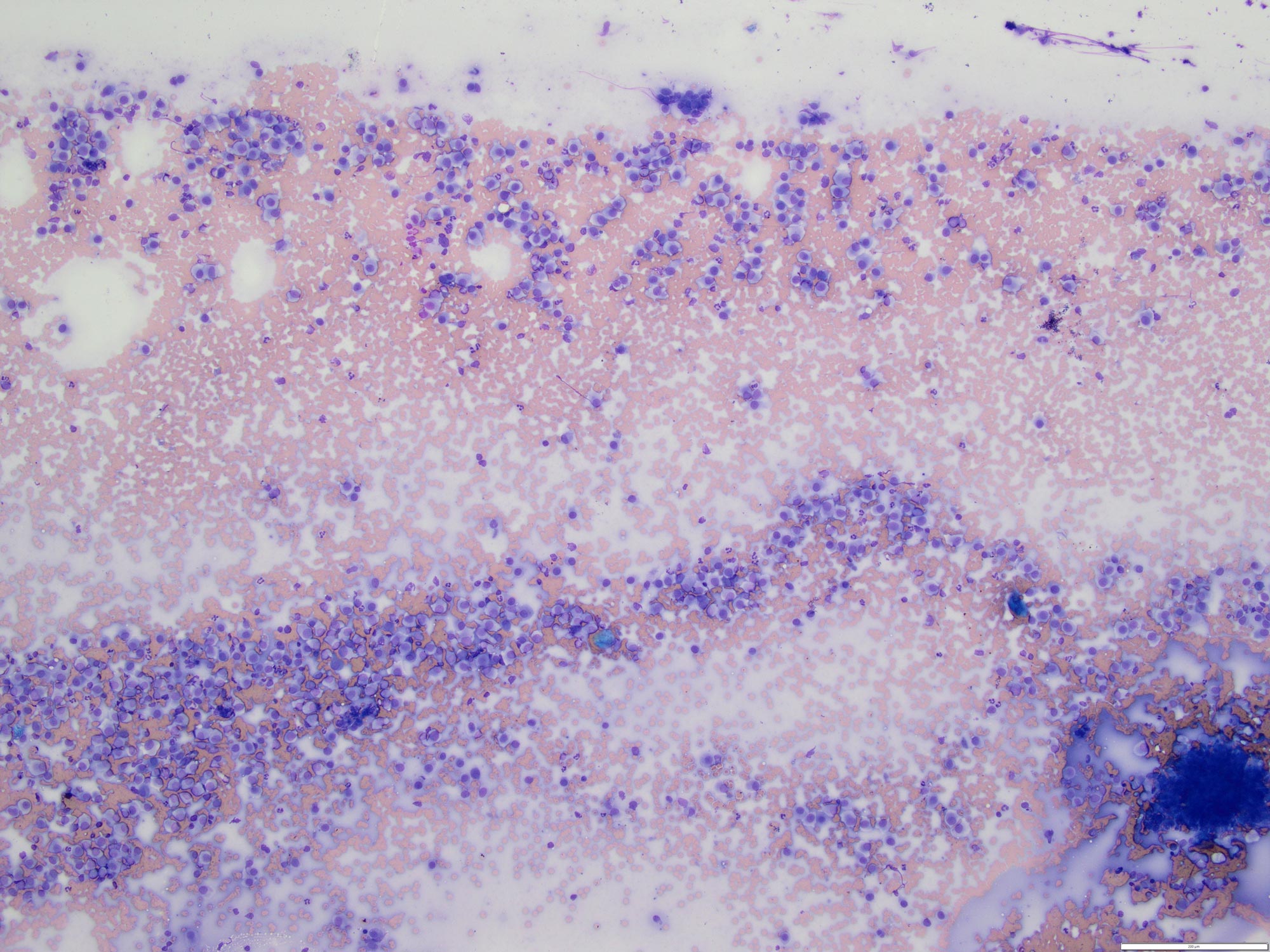

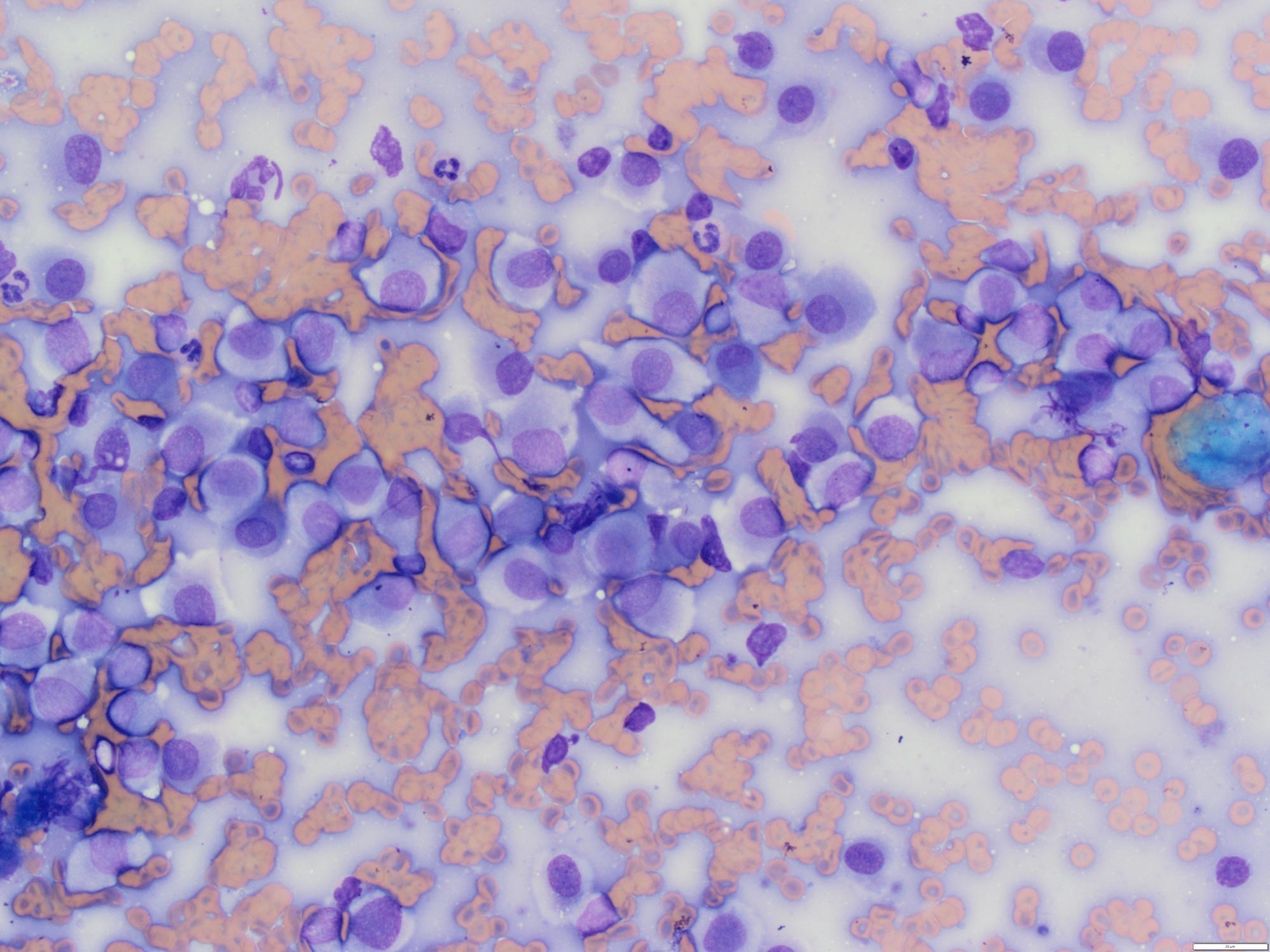

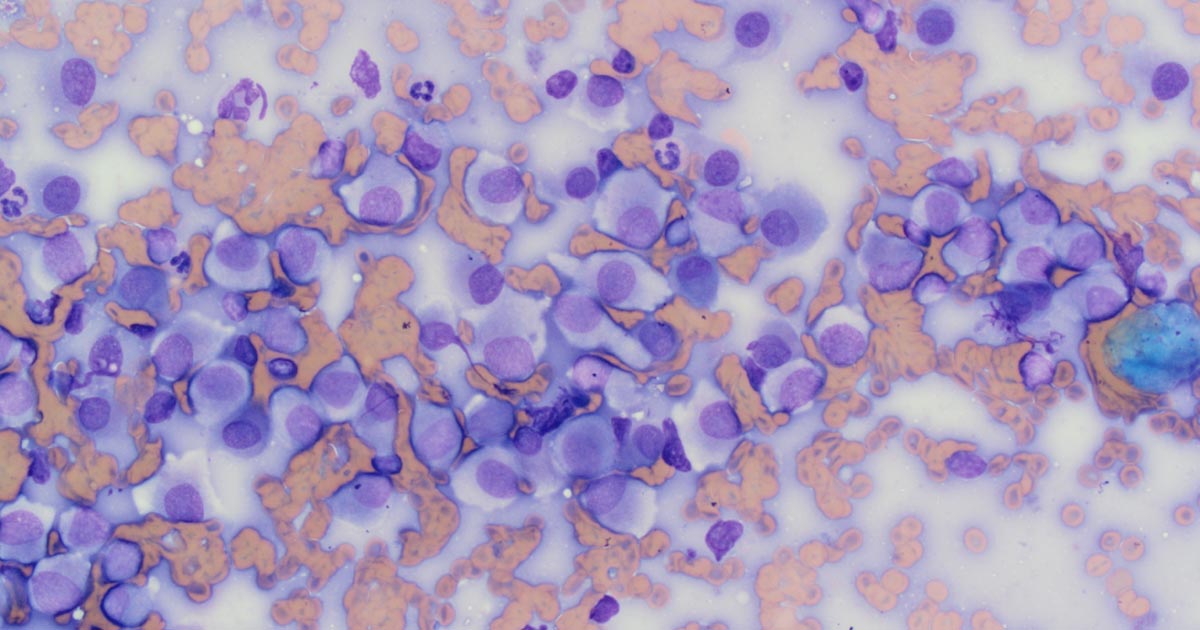

Round cell tumours don’t have much truck with each other. They are usually found as individual cells, and when they are found together. It’s rather like the crowds at Glastonbury – groups of strangers, close to each other but not connected.

Round cell tumours are the most diverse category of tumours – the category ranges from histiocytomas (benign growths of young dogs which usually regress by themselves within a few months), through lymphomas and mast cell tumours to malignant melanomas (one of the most aggressive tumours encountered in veterinary medicine).

Lesser known

A few other less common categories exist, too (neuroendocrine tumours, “blastomas” and so on), but the aforementioned covers the majority of neoplasia encountered in veterinary medicine.

As tumours become more aggressive, their mutations gradually regress the cells to a more primitive state; they resemble the tissue they are derived from less and less, and become “anaplastic” – anarchic bizarre cells that don’t look much like anything except bad news.

Back from Afghanistan

Hopefully that’s given you something of an insight into the wide ranges of disease that the term cancer covers, as well as going some way to explain what my day job involves.

And, finally, if I ever send you a report where I describe a population of “was in Kabul” cells, at least you’ll have some idea of what on Earth I’m talking about.

Leave a Reply