The next time you’re feeling a little rough from a cold, injury or abrasion, spare a thought for the humble neutrophil – the workhorse first responders of the immune system. The minor inconvenience you’re impatiently waiting to get better from has spelled the end for thousands of these plucky little cells.

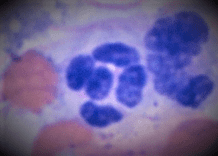

Here’s one of them now (right): a lobulated purple nucleus, like five oval pearls on a narrow string, with pale grey cytoplasm packed with near-invisible granules packed with death-dealing chemicals.

These beauties mature in their hundreds and thousands every day in the bone marrow, from where they are released into the bloodstream to roll around the edges of blood vessels via an ingenious group of molecules that work (in my own mind at least) rather like low-grade Velcro, slowing them down until they’re needed, whereupon chemical signals propel them to the site of injury and invasion, and to their doom.

Thousands of them.

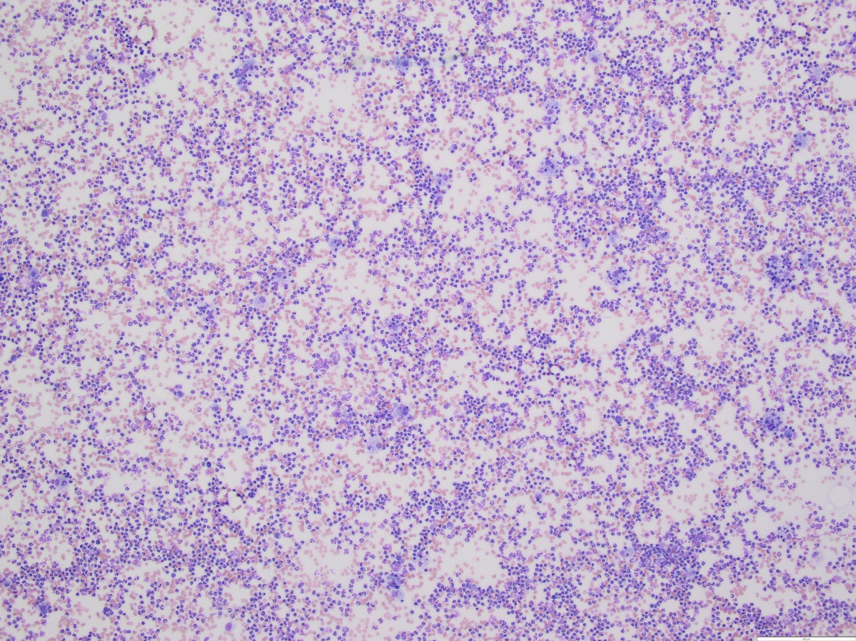

Here they are jammed into an abscess:

Cannon fodder

Unlike the mighty, near-unstoppable macrophage (some of which are also present in that abscess), neutrophils are largely one-shot packages. At the front line of the invasion or injury, they expel their payload of granules and attempt to eat any invading bacteria.

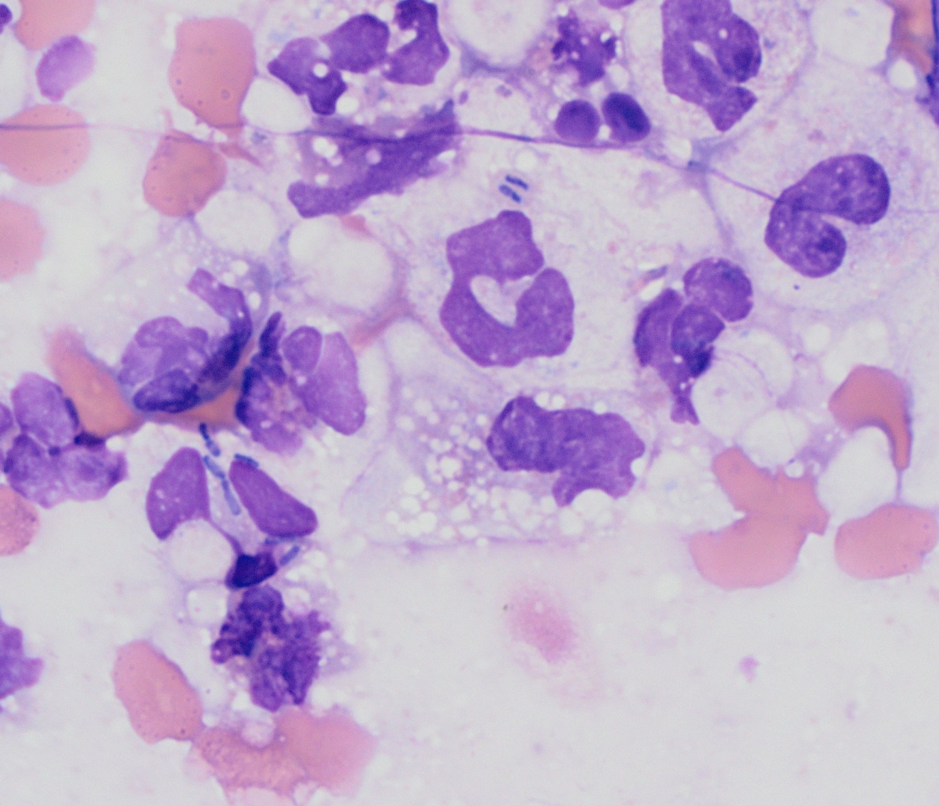

Here are a couple with their mission accomplished:

The short, dark rod-shaped things inside the cytoplasm of these neutrophils are bacteria, currently being assailed by a cocktail of toxic chemicals that is likely to be ruining their day.

Even out of granules and out of ammo, neutrophils have one last trick up their cytoplasm – neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are grenades studded with toxic granules that seek and destroy enemies, made from the nucleus of the neutrophil itself.

That’s right, as a last ditch resort, neutrophils fire their own brains out in a suicidal “screw you” to the invaders*.

Deploying child soldiers

Once deployed at a site of inflammation, and often bathed in a sea of bacterial toxins, neutrophils don’t have very long to live. Even if they don’t get drafted, neutrophils only stay in the circulation for a few days before they’re replaced by newer recruits.

When the war effort is going badly, band neutrophils and toxic neutrophils begin to appear in the circulation.

Band neutrophils

Band neutrophils are immature neutrophils; raw recruits rushed into circulation before they’ve completed their training. They haven’t had time for their nucleus to completely lobulate and so their nuclei appear more like a thick “band” – the most important clinical upshot of which is that they then have a tendency to occasionally roll into a remarkably phallic shape, much to the amusement of any clinical pathologists that happen to be looking at them (no picture supplied for this; use your imagination or Google it).

Toxic neutrophils

Similar to band neutrophils, toxic neutrophils have been rushed through basic training with little time for niceties, like completely removing early ribosomes or fully forming granules, leaving them with foamy or blue cytoplasm, or containing small fragments of ribonucleic acid (Döhle bodies). They are often bigger than mature neutrophils as they’ve had less time to divide.

Toxicity and bands are signs that inflammation is becoming intense and the body is desperately recruiting all the help it can get.

Mistaken identity

Neutrophils are an extremely common sight in cytological specimens – it’s a rare sample that doesn’t contain at least a handful of these plucky soldiers.

Although they are much less plastic and more distinctive than macrophages – and, consequently, less likely to confuse an idiot like me when I’m looking at my specimens – there are still a few pitfalls. As mentioned, toxic and/or band neutrophils are larger and bluer than normal, with less segmented nuclei… just like a monocyte. It can be very challenging to distinguish between monocytes and large toxic and/or band neutrophils in a peripheral blood film.

Similarly (if slightly annoyingly), neutrophils degenerate within fluid, which often makes their granules more visible, and more red, at least on Wright’s stain… just like an eosinophil. It can be frustratingly fiddly to tell the difference between a neutrophil and an eosinophil in some lung lavage samples – doubly frustrating as it’s often the difference between suspicion of bacterial infection or asthma.

Raise your glass

Despite these minor annoyances, it’s hard to feel much enmity towards the short-lived and valiant neutrophil. They’re a crucial part of our defences, unsung heroes, often overlooked in favour of more exciting cells due to their commonality.

The next time you’re feeling low because of some frustrating ache, pain or bug, raise a glass to your humble neutrophils. They might not always get it right, but they’re doing everything they can for you.

* Some recent research suggests that neutrophils actual survive this experience and don’t actually expel their entire nucleus, but this rather ruins the romanticism of the idea so I’m going to quietly ignore it.

Leave a Reply