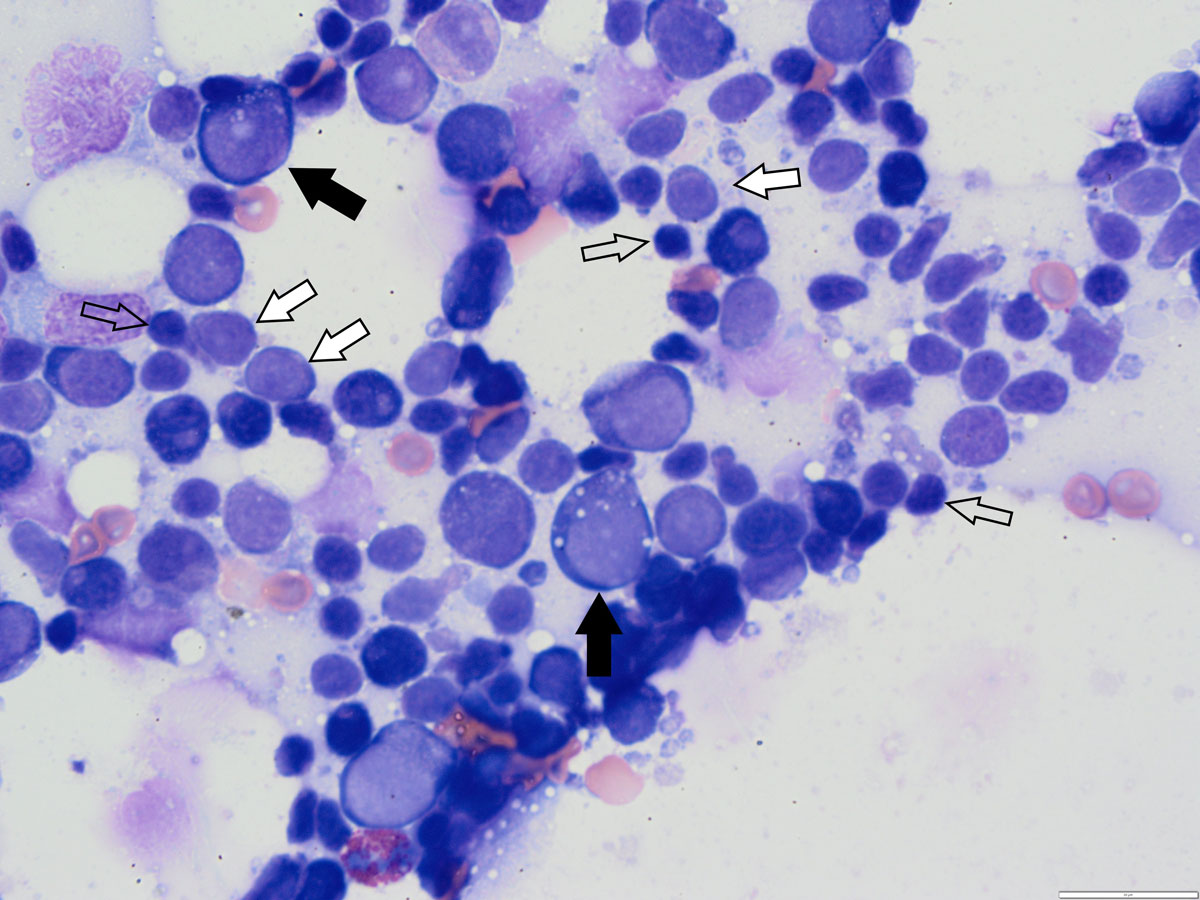

My job is full of beauty and wonder, but I must admit that, at first glance, lymphocytes aren’t much to look at. They come in all manner of varieties, but a standard-issue small lymphocyte is basically a tiny black dot with an almost indistinguishable small amount of cell juice (cytoplasm) around it.

A small lymphocyte contains pretty much the bare minimum of bits that an animal cell can have and still get away with being called a cell. Each one of those tiny dots – the nucleus – contains all of the instructions required to make an iguana, fruit bat or Louis XVI of France – all tightly compressed (hence the dense black dot) and largely inaccessible to cellular machinery.

Looks can be deceiving

Lymphocytes have a tale to tell that belies their basic appearance, however. They’re Jacks of all trades; their list of duties includes directly tackling invaders (although they leave most of this to neutrophils and macrophages) and patrolling cells and bumping them off if they display signs of cancer (or, rather more sinisterly, filling the cells with chemicals, which inform them to bump themselves off).

But their most important role (at least in mammals) is in the development of adaptive immunity – lymphocytes are largely responsible for the reason everyone is getting very excited about the prospect of a vaccine for the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. Oh, they’re also the reason you’re not dead already (assuming you aren’t; I’m sort of hoping this is a safe assumption if you’re reading this).

Scarily specific

Each one of those tiny dots will respond to a single specific antigen – antigens are basically a really, really tiny piece of something (usually something biological).

As you can imagine, a lot of somethings in the world can be broken down into tiny bits, and the fact that, whatever it is, you’ll almost certainly have a lymphocyte somewhere in your body that will react to it – and that your body will find a way of showing it to the right lymphocyte (as well as a lot of wrong ones) so your immune system will remember it the next time you meet it – is one of those miracles of evolution, wonderfully commonplace in biology, that makes you dizzy when you actually grasp what is happening.

The mechanism of how it’s all done is far too complicated to go into here, but I promise you, it’s just as wonderful as the basic idea.

Chick flick(ish)

In some respects, lymphocytes are hopeful romantics, gifted with a unique receptor and waiting, endlessly waiting, for that special antigen to come along and make their life complete. They’re the Bridget Joneses of the immune system, and when they finally meet the little chunk of biological material that excites them, they choose their final career path. Their DNA begins to open up, leading to larger lymphocytes with paler nuclei – intermediate and large lymphocytes.

Unlike Bridget Jones, however, when they meet their star-crossed antigen, they dedicate the rest of their lives to helping eradicate them from the face of the planet – or at least the body that they live in.

What’s in a name?

Lymphocytes are broadly classified into three groups – T, B, and NK. T and B cells are named after the places they were first discovered – T stands for “thymus” and B stands for “bursa of Fabricius”.

Frustratingly, the bursa of Fabricius is an organ only found in birds, which makes B lymphocytes in mammals sound like Americans who describe themselves as “Irish” despite not having set foot on the Emerald Isle for three generations. Fortunately, B lymphocytes are mainly found in bone marrow in mammals, so we can pretend that’s what the B meant all along.

NK stands for “natural killer”, which is something of a break in the naming tradition; I suspect Quentin Tarantino had something to do with it.

What they do

B cells make antibodies – floating miracles of protein engineering that attach to the specific antigen for which they have been made. Antigen-antibody binding triggers a number of different events, which are (again) complicated and varied, but the upshot of which is to make it much easier for the rest of the immune system to deal with the intruders.

T cells are the backbone of adaptive immune response. They are split into:

- Attack lymphocytes (CD8 lymphocytes – so called because of a surface marker they express – and, as I need to remember this for an exam, I remember they are “eight-ack” cells), which get all up in the face of any cells carrying the offending antigens.

- Helper lymphocytes (CD4 – which I unhelpfully remember by them being “not the CD8 ones”, but I suppose you could remember that they do things “four” other lymphocytes?), which play a huge role behind the scenes coordinating responses, and helping to prevent lymphocytes getting a bit carried away and attacking bits of the body they’re living in by mistake (spoiler: they are not always successful at this).

NK cells aren’t part of the adaptive system. They have the jobs I mentioned above – killing invaders directly and patrolling cells for cancer – although, this being biology, it’s a fair bet they also do dozens of other things we don’t realise – half of which directly oppose the other half (for the express purpose of confusing future students who are about to sit exams on them).

Perfection

Lymphocytes may look boring, but they’re the most varied, fascinating and vital components of the whole immune system.

I’ve used the word “miracle” a few times in this blog, but it’s hard to think of another word that explains them better. They’re wonderful, finely tuned and they’ve kept you alive this far, I promise you. The mechanisms behind their mode of action are so perfectly regulated; so carefully controlled, that when you learn about them you have to ask yourself: “Such a wonderful and complex system could never go wrong, could it?”

Of course it bloody could. Next time: when Bridget Jones attacks.

Hope to see you then!

Leave a Reply