Welcome back to lymphocyte talk. Now, sit still. Don’t fidget. We’re going to learn about what happens when lymphocytes go wrong.

Last time, I likened lymphocytes to lovelorn Bridget Joneses, forever searching for the antigen that fits their unique receptor, and then (perhaps a bit less like Bridget Jones) trying to destroy them. They have various ways of doing it, which we talked about last time, but the problem for lymphocytes is this: there are only a handful of lymphocytes in the body specific for each antigen that might invade.

What good are a few cells against an invading army? A trickle of antibodies or a few plucky soldier lymphocytes aren’t going to last very long against a full-blown Operation Sea Lion.

Lymphocytes solve this problem by doing what most of us spend much of our lives trying to do: making copies of themselves.

Me, myself and I

When they meet their one true antigen, lymphocytes undergo clonal expansion – which is exactly what it sounds like; they make lots and lots of identical versions of these. Most of them are enlisted into the ongoing fight, but a few remain behind the front lines as memory cells.

These memory cells, like ageing veterans, sit in lymph nodes and lymphoid nodules and bore the younger lymphocytes silly with tales about the previous invasion, and if that particular antigen ever dares to set pseudopod into the body again, they rapidly clone themselves. This means subsequent immune responses to the same antigen are faster and stronger than the first, and it’s why vaccines work (not that we all suddenly have vaccines on our mind for any particular reason or anything).

It’s a beautiful, elegant system. However, like everything else in biology, it can go wrong – and when it does, it can be catastrophic.

When good goes bad

You see, the lymphocyte ability to clone themselves is great when your body has an invader that needs clearing, but greatly increasing a cell’s ability to replicate and removing many of the limits on it may ring a few alarm bells, because that’s dangerously close to the definition of cancer.

You wouldn’t be wrong to be alarmed, because, despite evolution’s efforts to produce a highly specific receptor that needs to be triggered before this happens, every so often lymphocytes get tired of waiting, mutate and activate themselves without ever meeting their special someone.

Let’s be honest, we’ve probably all done something similar, but when lymphocytes do it, the consequences are… well, I have a very visual job, so let me show you.

In a lymph node far, far away

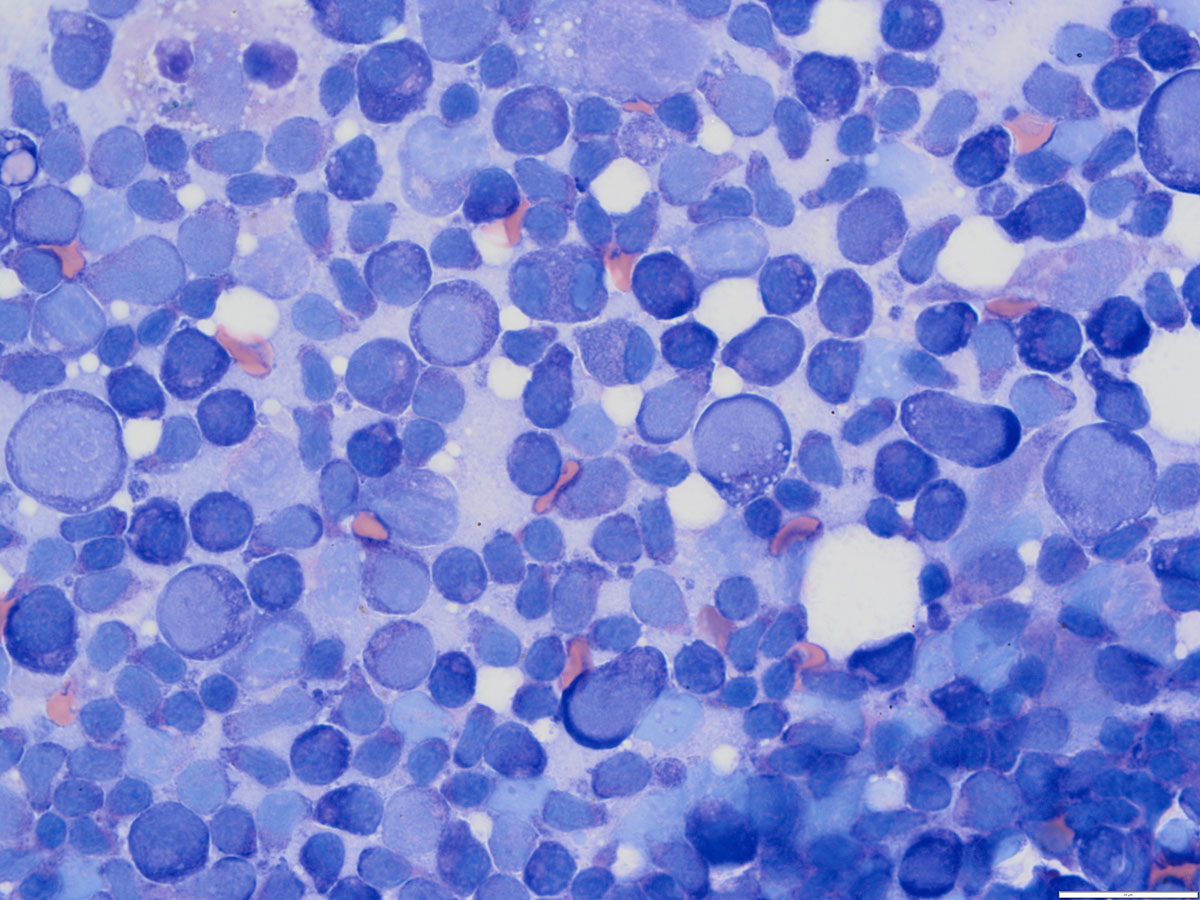

Below is a normal lymph node, a melting pot of different cells. Most of them are bland small lymphocytes, but there are a lot of intermediate cells and large cells too, all living together happily. There’s a cell dividing, but cells are allowed to do that (at least to a limited extent).

The point is, everyone is different. If you’re like me, you can probably hear the Star Wars “cantina band” music playing in the background as you look at them (but then, if you’re like me, you can probably hear this pretty much all the time anyway).

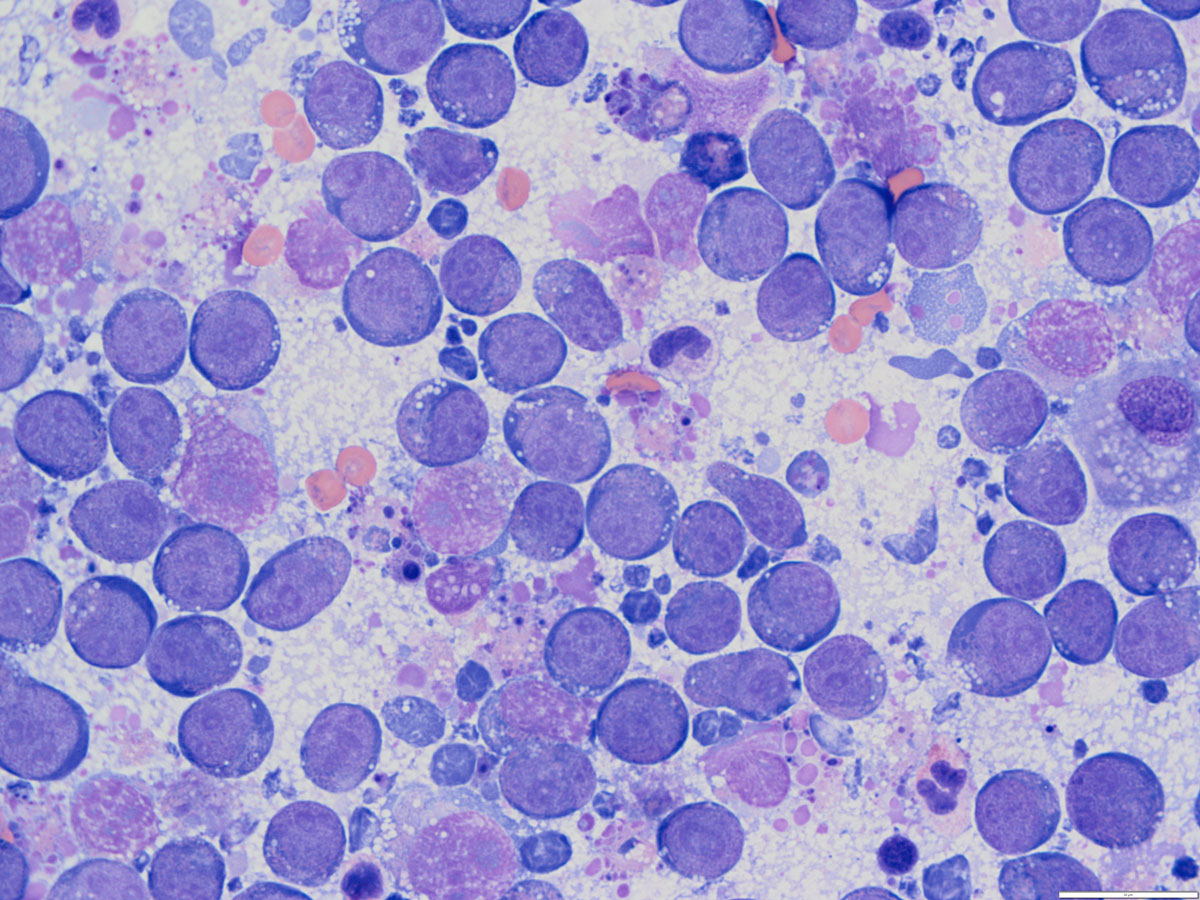

But here’s a lymph node where things aren’t quite going to plan.

Have a look…

See? It’s like a redneck wedding. Everyone looks the same because they are basically the same person… well, lymphocyte. There are a few nervous-looking small lymphocytes, but most of the cells are those big blue ugly suckers, with open and suspiciously-active nuclei.

I mentioned cancer before, and that’s exactly what is going on here – these are neoplastic (cancerous) lymphocytes. When it happens in a lymph node, or as a solid mass in an organ, we call it lymphoma. When the rebellious lymphocytes are in the bone marrow, we call it leukaemia (well, more specifically lymphoid leukaemia, because you can get other blood and bone marrow cancers too), but like most biological definitions, this one is a little woolly around the edges – lymphoma can end up in the blood, and leukaemic cells can seed into lymph nodes, but by then it doesn’t really matter what you call it, it’s pretty bad news.

No laughing matter

Our bodies have a lot of mechanisms of dealing with rogue lymphocytes like those above, and most of them don’t make it very far before they’re destroyed – we think. A little like terrorist attacks, we only really notice the ones that don’t get stopped. In my previous post, I discussed B and T lymphocytes, and there’s an old not-really-much-of-a joke that, at least when you’re talking about lymphoma: B stands for “bad” and T stands for “terrible”

As a rule, it’s broadly true – T-cell lymphoma tends to be more aggressive and less responsive to chemotherapy – but there a so many exceptions to it that it isn’t really all that useful a rule, and it’s certainly not a very good joke.

It’s a shame such a wonderful system that has kept us all alive so far can go so badly wrong, and at least in veterinary medicine it seems to go wrong quite often – it may reflect the case load at the lab I work at, but lymphoma is the most common cancer we diagnose by quite some way.

What’s next?

Fortunately, there are lots of things we can do about it – lymphoma is much more responsive to chemotherapy than many other tumours are, and although cures are unlikely in veterinary medicine (unlike human medicine), therapeutic drugs certainly can give patients a normal quality of life for quite some time.

Well, we’ve talked about what happens why lymphocytes get things right, and what happens when they don’t. For a final blog in this series, I’m going to have a little look at some other diagnostic tests (other than my beloved cytology, that is – I’m thinking of PARR, flow cytometry, and immunophenotyping) which help us work out exactly what’s going on.

See you in a few weeks for that one!

Leave a Reply