I’m going to briefly touch upon three extra tests that can help to diagnose lymphoma or lymphoid leukaemia, at least in veterinary medicine.

I say “briefly” because they are all complex and highly specialised procedures, all of which I obviously have absolute and full understanding of, but sadly don’t have space to discuss here. Oh well…

Anyway, all three of the tests I’m going to mention have essentially the same idea – these tests are used to identify whether the lymphocytes are all basically the same cell (and therefore cancerous), or whether they are very mixed with no particularly prominent population, and therefore reactive.

Let’s have a peek at them…

PARR

PARR stands for “PCR testing for Antigen Receptor Rearrangement” (you can use this to impress your friends at parties… or should I say PARRties? Ahem, anyway…). Let’s break that down into some more digestible chunks.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is probably something you’ve already heard of – it’s the mainstay, at least at the time of writing, of Covid-19 testing. It’s a method of finding a small amount of DNA (or RNA) in a sample and massively multiplying it so it can be detected by the test equipment.

Receptor detector

In the PARR test, the DNA amplified is that which encodes lymphocytes’ unique receptor – the one that is highly specific for a single antigen (see here). In a normal group of lymphocytes, there should be thousands of slightly different strands of DNA, all coding for receptors looking for different antigens. In a group of clones, all those lymphocytes have the same antigen receptor, leading to a single prominent spike in the results.

PARR is a direct test for “clonality” and it’s an extremely useful test because it can be performed on many different samples, including blood, fluids, and – most usefully from my perspective – cytology slides that have already been stained.

It’s not foolproof, sadly – what in biology ever is? There are rare infections that can stimulate a clonal, or at least nearly-clonal, population of lymphocytes, leading to false positives. Some cancer cells have such a blatant disregard for biological norms that they don’t even have receptors – or they have receptors so mutated that the PARR analysis can’t find them, leading to false negatives.

Also, the test is not reliable at distinguishing between B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes (some neoplasms look like B-cells genetically but express T-cell surface markers, and vice versa – look, I told you it was complicated).

Immunocytochemistry / immunohistochemistry

These two are basically the same test, except that immunocytochemistry is performed on cytology specimens (the ones you suck out of an animal with a needle and squirt on to a slide), and immunohistochemistry is on histology specimens (the ones you chop out of an animal with a scalpel and drop into formalin).

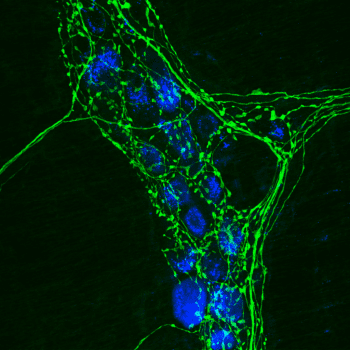

They both involve staining the slides produced with dyes that attach to specific antigens on the cells that have been squished onto them – in this case, they attach to surface proteins that identify the type of cell.

What kind?

There are lots of different antigens available, but when we’re looking for lymphoma or leukaemia we’re most interested in whether these cells are T-cells, B-cells, immature cells or cells that express unusual markers (such as T-cells which also express proteins that only B-cells should carry).

Importantly, these dyes are not specific for the receptors of the cells; they can only tell you which broad class of cells are present. You’re not looking for clones here, just the overall make-up of the population. That means you can be very suspicious of cancer if almost every cell present is the same class of cell, but it’s less definitive than PARR.

The main difference between the two tests is that PARR is more use at telling you whether cancer is present or not, and immunochemistry is more useful at categorising the cancer once you already know it’s there. These are pretty broad strokes, though, with considerable overlap.

Flow cytometry

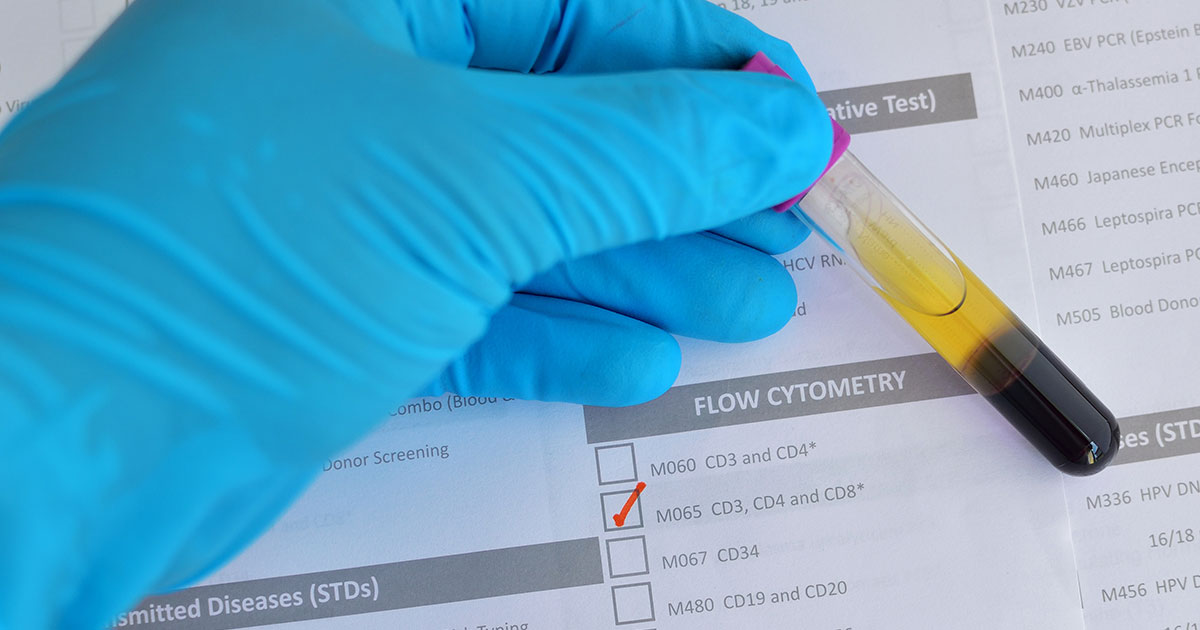

Although the technique used is very different (flow cytometry measures physical and chemical properties of cells – such as their density and electrical impedance – to identify them, using the same technology found in automated haematology analysers), flow gives similar results to immunochemistry; that is, this technique characterises cell type rather than looking for clones.

However, as flow cytometers analyse thousands of cells rather than hundreds (as immunochemistry does), they provide much more detailed and specific information on the cells present.

Again, the information is more useful in characterising a cancer you already know is present, but, as before, there is overlap and flow can be very useful to confirm suspicions.

Negatives

The main disadvantage of flow cytometry is it requires a liquid suspension of cells; this is fine when the suspect cells are floating around the bloodstream, but trickier when cells are present in a solid mass, as with lymphoma.

Cells can be suspended in a special fluid, but it’s a limitation that means flow cytometry is not used as often as the preceding two techniques – or at least, not yet. As the technology advances and becomes more widespread, almost all cancers (not just those of lymphocytes) are likely to be categorised by their surface markers, as it has implications for their response to chemotherapy.

Four long blogs

It’s taken me four blog posts to give you a brief overview of lymphocyte functions, one of the things that can go wrong with them (there are many more) and a few examples of how to diagnose the problems (although I’m sure you agree that cytology is definitely the coolest one; not that I’m biased or anything).

You can revisit the first three here:

- Lymphocytes, part 1: Bridget Jones

- Lymphocytes, part 2: Attack of the Clones

- Lymphocytes, part 3: Jane Austen’s mirror

Four blogs and we’ve barely even scratched the surface, this is how complex and wonderful lymphocytes are.

I am aware that, to a first approximation, cytology is just a load of blue and purple blobs. I hope these blogs, if nothing else, help to remind you of the wonder and potential that each one of those tiny dots contains.

Leave a Reply