Gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) is a true veterinary emergency and while it can be daunting to be presented with a sick dog with suspected GDV, the most important thing to remember is this patient will likely succumb to this condition without your intervention.

First, a little pathophysiology: GDV is a broad term that can refer to gastric dilation on its own, gastric dilation with volvulus, and even chronic gastric volvulus. These conditions usually present in large or giant breeds and we still know little about the underlying causes.

Once dilation and volvulus occurs, perfusion to the stomach and other abdominal organs is compromised. Along with general shock – which can be fatal in its own right – decreased stomach wall perfusion can result in stomach wall necrosis, rupture and peritonitis.

Clinical signs

Quite often, a GDV case starts with a telephone call from a panicking owner. He or she usually reports an acute onset of retching, regurgitation or vomiting in their large or giant breed dog after feeding.

Other common signs include:

- hypersalivation

- agitation

- palpable abdominal distension

When presented, many of these cases will be obvious and the animal already in some degree of shock. You need to institute fluid resuscitation and gastric decompression immediately to restore perfusion as soon as possible.

Confirmation

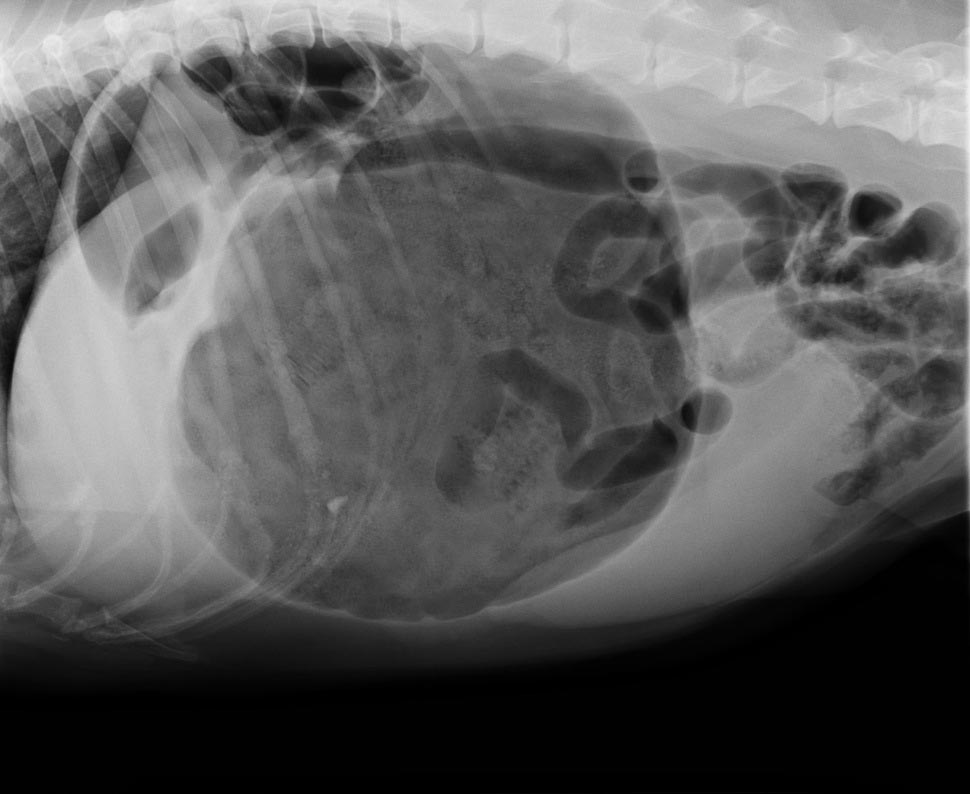

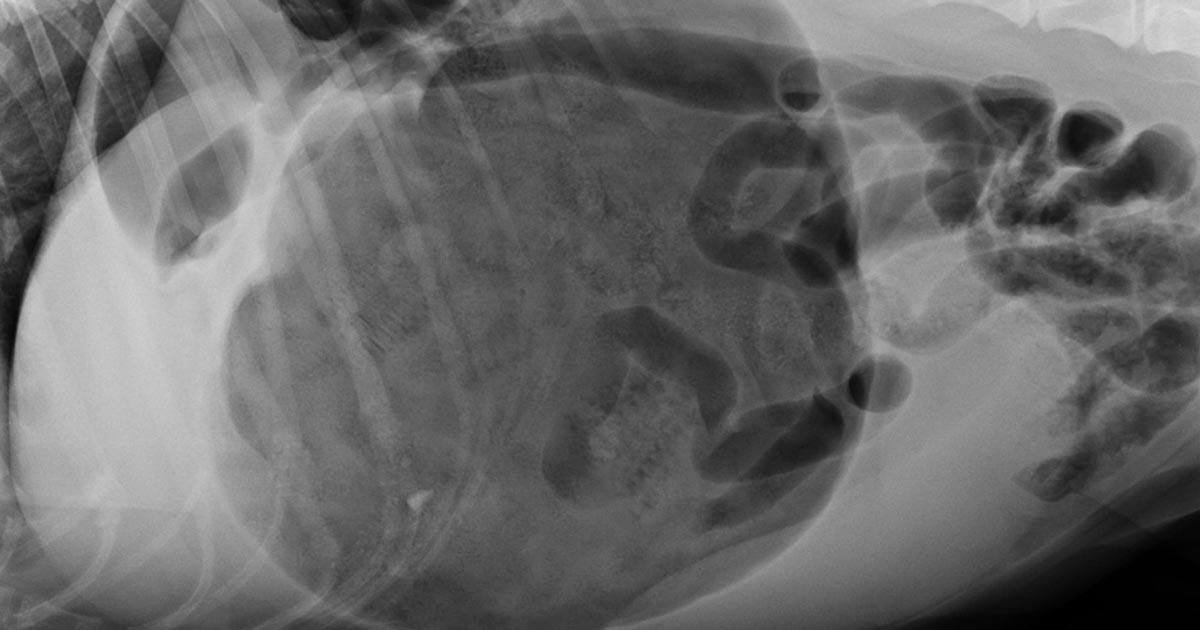

To confirm the patient truly has GDV, as some patients may present with simple gastric dilation from over-engorgement, you need to perform an abdominal radiograph.

Always keep an eye out for the large, deep-chested dog that presents with vomiting or retching, but doesn’t appear bloated. Don’t be fooled into ruling out GDV in these patients based on physical examination alone – often, no visible or palpable gastric distension exists as the ribs cover the stomach. That is where the abdominal radiographs play an especially important role.

It is common practice at our hospital to perform abdominal radiographs as soon as possible, so as to not miss a hidden or subtle GDV in these large breed dogs.

Which view is best?

The classic approach is to lie the patient in right-lateral recumbency, in this view, you would see the classic “Smurf’s hat”, “boxing glove”, “Popeye’s arm”, “double bubble”, etc. This is compartmentalisation of the stomach, indicating not only gastric dilatation, but volvulus as well.

You should also look for evidence of pneumoperitoneum, as it may suggest gastric wall rupture.

At this stage, it is also important to collect blood for biochemistry, haematology, electrolytes and, if available to you, blood gas analysis. ECG readings should also be taken to determine if the patient has any life-threatening arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia.

Next month, we will talk about stabilising and treating these patients.

- Gerardo Poli is the author of The MiniVet Guide to Companion Animal Medicine – now available in the UK.

Leave a Reply