Following on closely from the first two parts of our February focus on gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) – which covered IV fluid resuscitation, pain relief and gastric decompression – we turn to surgery.

Here, I offer a few tips to help ensure the procedure runs as smoothly as possible.

Abdominal incision

Make the abdominal incision large – from the xipoid to the pubis. You cannot perform a proper exploratory laparotomy without proper visualisation. Additionally, when it comes time to re-rotate the spleen, you will need all the space you can get. Removal the falciform fat to help improve exposure.

Derotation

The degree of rotation is variable from 90° to 360°, so not all GDV surgeries will be the same. If the omentum is draped over the stomach, this is pathognomonic for GDV.

When derotating, stand on the right side of the patient as all descriptions are based with the surgeon on that side.

During volvulus, the pylorus rotates ventrally then to across to the left side of the body.

Method

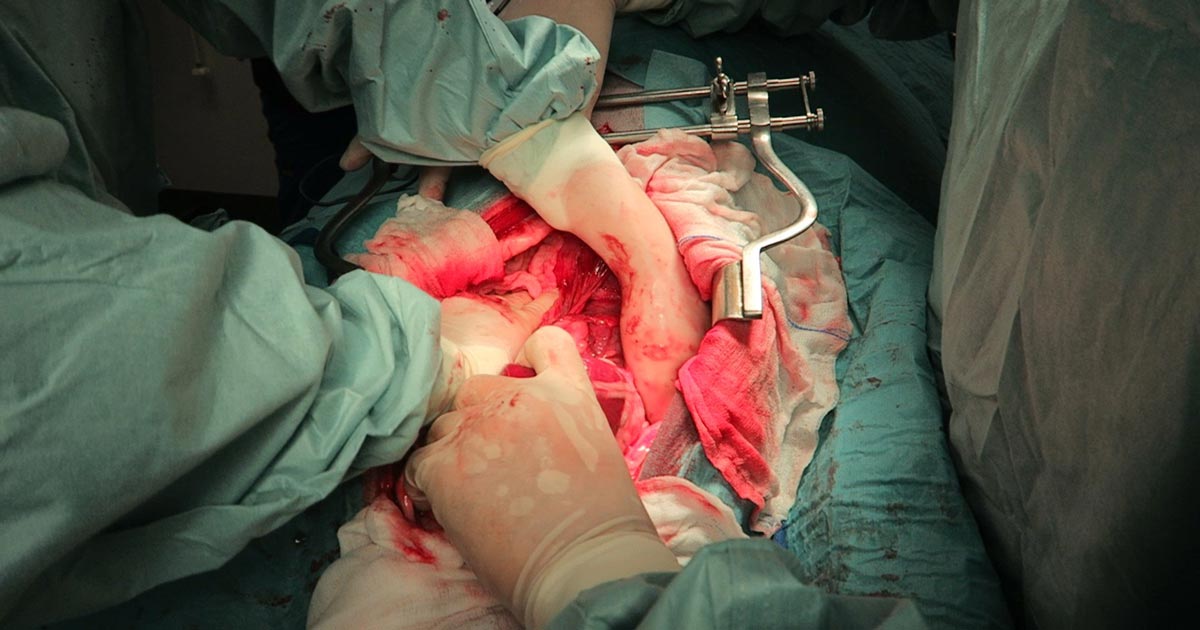

With one hand (usually your right) reach down the left abdominal wall and firmly grab the stomach down where the spleen normally resides, then pull towards you (Figure 1). At the same time, use your other hand to apply downward pressure (or pressure in the dorsal direction) on the right side of the stomach. This simultaneous pulling on the left side of the stomach and push on the right side of the stomach is generally successful.

At this stage, it is important to check things have gone back to their normal places. Ensure the:

- pylorus is to the right and you are able to track it through to the duodenum and pancreas

- fundus is to the left

- omentum is hanging off the caudal aspect of the stomach

- spleen is also derotated

Passing a stomach tube can sometimes help you identify the oesophagus – you can feel it running along the inside of the gastric cardia and fundus.

Further decompression

If the stomach is still distended and hard to manipulate, reducing the size of the stomach can make derotation significantly easier. Pass the stomach tube again or aspirate more gas from the stomach using a 18G needle, extension set, 50ml syringe and three-way tap.

Assessment of the stomach

Gastric necrosis is most likely to occur along the greater curvature of the body and fundus. Lifting up the stomach and looking at the dorsal aspect of these areas is important. Allow 5 to 10 minutes after derotation before resecting the affected areas to see if it regains colour and pulsations.

Pexy

I personally perform incisional gastropexy – I find them easier and very effective. I find an area on the pyloric region of the stomach where minimal tension exists, when brought to the lateral body wall (Figures 2 and 3).

Ensure you do not accidentally incise into the diaphragm; the muscle fibres of the diaphragm radiate out and insert at the costal arch. Identify the transverse abdominal muscles and pexy the stomach to here.

I also ensure muscularis to abdominal muscle contact to increase the strength of the pexy once it is healed.

Spleen

The spleen is almost always engorged in GDV cases, but this does not necessarily mean it needs to be removed.

Always assess the splenic blood supply as it is not uncommon for splenic vessels to tear or thrombose during the volvulus.

If there is any concern that the splenic arterial flow is compromised, I would perform a splenectomy.

Stomach still dilated after pexy?

What if the stomach appears to be still dilated? Generally, once the stomach is derotated, normal anatomy has been achieved and the pexy is performed, the remaining food and gas will pass with time. You can try to empty more via a stomach tube or aspiration with a large needle, but this is not generally required. I would not perform a gastrotomy to remove contents.

Next week, we will cover common postoperative complications.

>>> Read Focus on GDV, part 4: the recovery

Leave a Reply