Postoperatively, gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV) patients remain in our intensive care unit for at least two to three days.

Monitoring includes standard general physical examination parameters, invasive arterial blood pressures, ECG, urine output via urinary catheter and pain scoring.

I repeat PCV/total protein, lactate, blood gas and activated clotting times (ACT) immediately postoperatively and then every 8-12 hours, depending on abnormalities and patient progress.

I always repeat these blood tests postoperatively, as IV fluids given during the resuscitation and intraoperative period often cause derangements. I use the results to guide my fluid therapy, but also take it with a grain of salt.

IV fluids

I generally continue a balanced and buffered crystalloid. The rate depends on blood pressures, urine output and assessment of general physical examination parameters for perfusion and hydration, but I try to avoid fluid overload and reduce the IV fluids postoperatively as soon as possible.

Coagulopathy

Prolonged clotting times are frequently seen as a result of consumption in a dog with GDV. However, one should note it can also occur as the result of haemodilution.

As the underlying disease process has been corrected, and haemostasis achieved during surgery, I usually monitor ACTs, but may not necessarily treat with blood products as prolonged ACTs do not always translate to clinical bleeding. Unless clinical evidence of bleeding exists, I generally hold off treatment and monitor.

Hypoproteinaemia

Low total protein is also common. This is generally due to haemodilution from fluid resuscitation. However, a low total protein does not mean oedema will develop, or that it requires management. I generally track the protein levels, use conservative fluid therapy and try to correct it by instituting enteral nutrition as soon as possible.

Electrolyte imbalances

Hypokalaemia is a common complication of fluid therapy. This can be rectified with potassium supplementation in the IV fluids.

Hyperlactataemia

If present post-surgery, this is usually corrected with a fluid bolus. However, I always assess for other things that may affect oxygen delivery to the tissues, such as poor cardiac output (arrthymias), hypoxaemia (respiratory disease) and anaemia (from surgical blood loss).

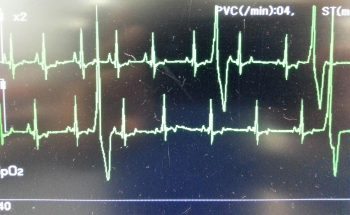

Arrhythmias

Ventricular arrhythmias are common post-surgery. Accelerated idioventricular rhythms are the most common cause, especially if a splenectomy was performed.

Before reaching for anti-arrythmia medications, first check and correct:

- electrolyte abnormalities

- hypoxaemia

- pain control

- hypovolaemia or hypotension

If they are still present, despite correction of the above, consider treating the rhythm if:

- multifocal beats (ventricular premature contractions of various sizes)

- overall rate greater than 190 beats per minute

- R-on-T phenomenon

- low blood pressure during a run of ventricular premature contractions

I start with a bolus 2mg/kg lidocaine IV and start a constant-rate infusion of 50ug/kg/min to 75ug/kg/min.

Anaemia

It is common to have a mild anaemia post-surgery, due to a combination of blood loss and haemodilution. In the absence of transfusion triggers – such as increased heart rate, increased respiratory rate or hyperlactataemia – it does not require treatment.

Vomiting

Anti-emetics are the first line of medication. Non-prokinetic anti-emetics, such as maropitant and ondansetron, can be used immediately; otherwise, after 12 hours, metoclopramide can also be used postoperatively. If the patient remains nauseous despite these medications, the placement of a nasogastric tube can ease nausea by removing static gastric fluid.

Excessive pain relief may also contribute to the nauseous state.

Pain relief

I mostly rely on potent-pure opioid agonists, such as fentanyl constant-rate infusions and patches. This is generally sufficient for most patients. Ketamine is occasionally used.

- Some drugs listed in this article are used under the cascade.

Leave a Reply