Prolonged hypoxaemia, hypotension and hypoventilation are the top three causes of periparturient fetal mortality – for these reasons, all precautions must be taken to avoid it.

As soon as authorisation has been obtained to proceed with a caesarean section, the patient should be stabilised immediately. This includes having perioperative blood work performed, and clinical hypoperfusion (common in patients that have gone through prolonged stage two labour) and hypotension corrected as soon as possible, usually with fluid boluses.

While fluid deficits are being corrected, preoperative monitoring and surgical site preparation (clipping and the initial stages of surgical scrub) can be performed with the patient still conscious. This will significantly reduce the time the patient is anaesthetised, as isoflurane potentiates hypotension.

Physiological changes

A few physiological changes in periparturient patients must be considered before anaesthetising them.

Higher oxygen demand

Firstly, pregnant animals have a higher oxygen demand due to the developing fetuses. However, due to their large gravid uteruses, they have decreased functional residual capacity and total lung volume. This is further exacerbated when animals are placed in dorsal recumbency, with increased pressure on their diaphragms.

For this reason, pregnant animals should always be preoxygenated prior to induction – with as much of the patient preparation completed – to reduce the risk of hypoxaemia. This is one of the main reasons the time from induction to delivery of the puppies should be as short as possible.

Sensitivity to anaesthetic agents

Secondly, pregnant animals have an increased sensitivity to anaesthetic agents. Blood volume and cardiac output also increase dramatically during pregnancy; therefore, if blood loss occurs and blood pressure is not maintained, significant hypotension can occur.

Any medication that crosses the blood-brain barrier will equally cross the placental barrier; therefore, the effect of medications can be reduced by a few things. Firstly, the use of local anaesthetics (such as epidurals) can be employed to minimise inhalation anaesthetics, thus their hypotensive effects. Always use minimal drug dosages that achieve the desired effect. Short-acting, rapidly metabolised drugs and reversible drugs should be used whenever possible.

Don’t premedicate

Premedication of caesarean patients is strictly avoided at our hospital. Acepromazine can result in hypotension and has a long duration of action, while opioids can cause potent respiratory depressants in unborn fetuses as it crosses the placenta.

Puppies and kittens born heavily narcotised or sedated will have bradycardia and may not take spontaneous breaths, further increasing the risk of mortality.

Speedy delivery

Once the patient has been induced, the speed of delivering the fetuses is of paramount importance. Inhalant anaeshetics causes maternal vasodilation and decreases uterine blood flow, as well as neonatal depression.

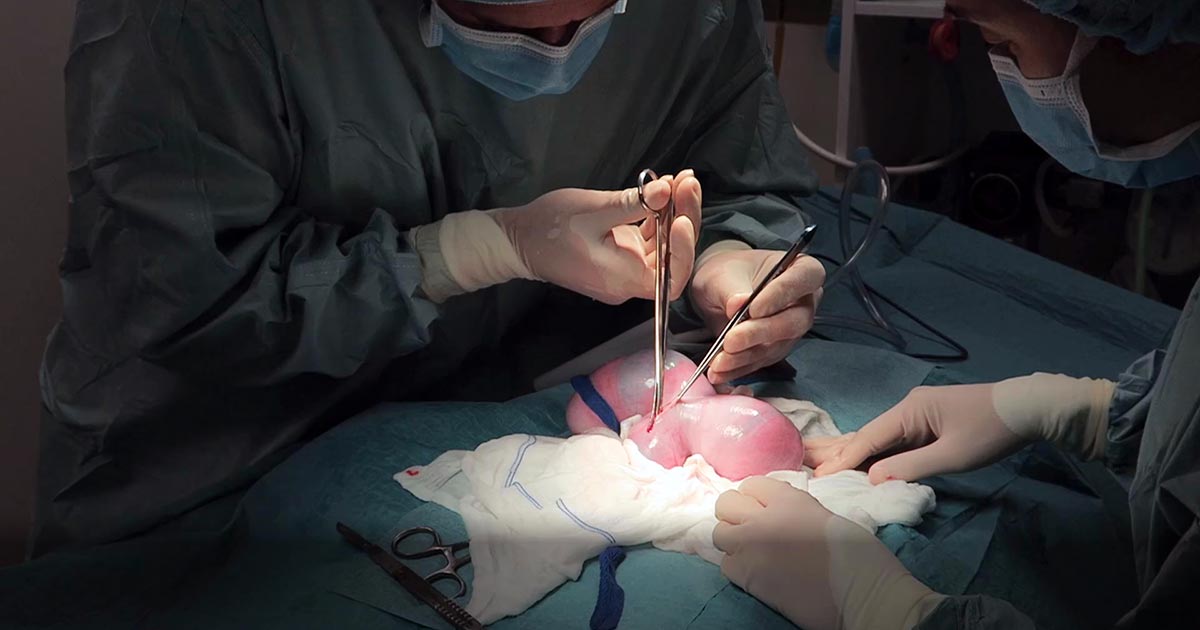

Making a large abdominal incision is highly advised, despite the fact it may take longer to close, as it enables faster and more gentle manipulation of a large fetus-filled uterus.

The traditional caesarean technique involves a single incision in the uterine body. Fetuses should be gently squeezed towards the incision. In patients with many fetuses, especially large-breed dogs, making a single uterine body incision may significantly delay delivery of the fetuses. Concern also exists with excessive traction and manipulation of uterine blood vessels when trying to manipulate the fetuses to the uterine body incision. In these cases, additional incisions in the uterine horns can be made.

With this method, surgical time for closure will be longer and considered carefully in patients where future breeding is likely, as the risks of adhesions and uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies increases compared to the single uterine body incision method.

Closure of the uterine wall should always be in two layers – firstly, an appositional simple continuous pattern; followed by a second inverting (Cushing or Lembert) pattern.

Post-fetal removal

Once the fetuses have been removed, a few medications can be given safely intraoperatively.

Firstly, opioids are safe at this time. Fast analgesia can be achieved when the opioid is given IV. Oxytocin can also be administered during this time, but beware uterine involution and contraction will be immediate; therefore, close attention needs to be paid to the uterine sutures to ensure they have not become loose.

NSAIDs should be avoided in lactating queens and bitches, as most are excreted in the milk. Safety data has not been established in lactating animals, while previous animal studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus.

Tramadol, a synthetic opiate-like (μ receptor) agonist, has high analgesic effects. Tramadol and its active metabolite are known to enter maternal milk, albeit at very low levels. No animal reproduction studies exist to establish its safety in use in neonates, but it is an analgesic considered safe to use in young animals.

Conclusion

Caesarean section is the one emergency surgical procedure where speed is of essence.

With prompt stablisation, pre-induction surgical preparation, fast delivery of fetuses and avoidance of certain medications, the chances of survival of the already distressed fetuses can dramatically increase.

Leave a Reply