Several piles of paper are on the table in the centre of the room. The slide trays are stacked next to them; depending who has been on “winkling” duty, this is either a towering Manhattan skyline of ominous-looking pillars, or a sprawling shanty town of small groups and ordered by urgency, potential difficulty, quality of history and type of aspirate.

Around me, pathologists are speaking into their headsets: “Six slides of aspirates from a mass on the dorsal right fore are examined…

“The cells have, large, central nuclei, approximately two erythrocytes in diameter…

“These are slightly challenging cytological patterns to interpret; the overall appearance at low power is of…”

I have trained my software to recognise my voice (the software is called Dragon and I can’t tell you how excited I was on learning at least part of my job would be learning how to train my Dragon) and I am still entranced by the letters as they dance across my screen. It’s not quite perfect yet – last week, Dragon misinterpreted my pronunciation of “fructosamine” and I very nearly sent out a report that would have informed the bemused vet that “photos of me may be useful in investigating the possibility of diabetes mellitus further”. Narcissistic, even for me.

I take the first slide from the tray on my desk, labelled “L SM LN”, and slot it on my ‘scope (I mean microscope; I’m just trying to sound cool – please indulge me), still feeling the slight thrill of excitement as I turn the light on and lean down to examine this next puzzle. As I focus on the beautiful sight in front of me (one thing I never realised about cytology – just how gosh-darn pretty everything is), I think of the weekend locuming and the telephone conversation I had with a client explaining I thought it was time to let go because we had done all we can.

I love my job.

World of difference…

Nevertheless, it feels a long way from general practice. General practice is immediate, dirty, and messy. You can’t help but have a connection with your patients – they are physically there, in front of you. I love the puzzles, and the intensity and intellectuality of my lab work, but it can sometimes feel distancing. A world of difference exists between reading “eight-year-old German shepherd dog, male entire” on a submission form and having the bugger try to take your arm off in a consulting room.

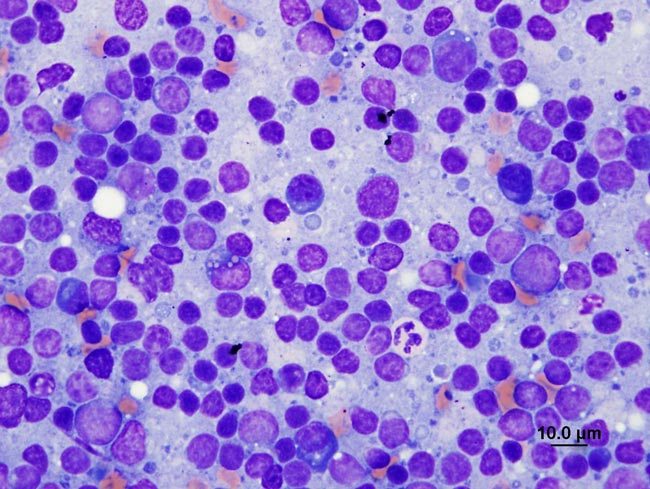

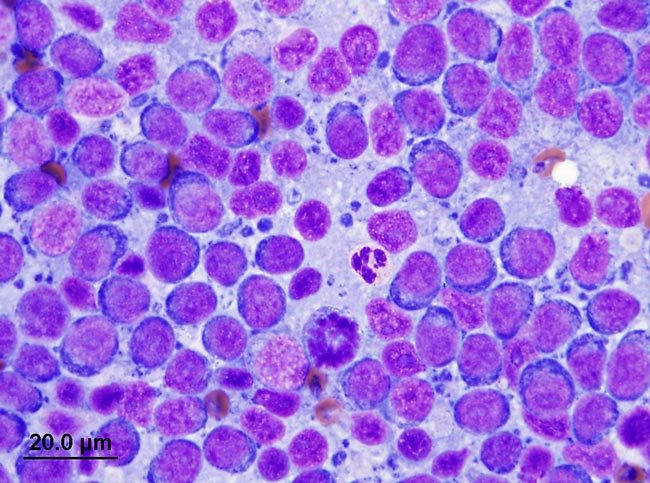

I peer down at the slide on my scope. Even at low power, it doesn’t look quite right. At higher power, it’s obvious. The normally mixed range of different-sized lymphocytes that make up the normal cell population of lymph nodes are absent. This slide is dominated by a single type of cell – large lymphocytes with open, active nuclei and more mitotic figures than have any right to be there.

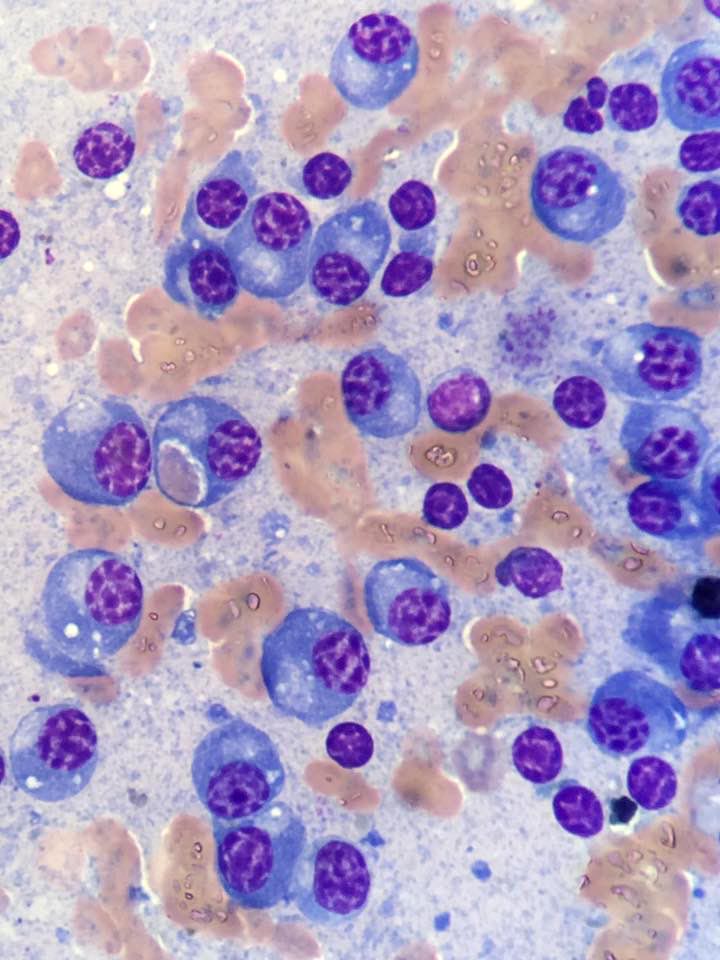

I scan around for plasma cells – my favourite cells, mature B-lymphocytes specialised in producing antibodies. They have cracked, purplish nuclei like a psychedelic river bed, and deep royal blue cytoplasm, topped off with a clear area next to their nucleus (the Golgi apparatus, prominent because it’s busy pumping out proteins to make immunoglobulins). These words fail to express how pretty they are, but if Prince was reincarnated as a part of the immune system, there’s no doubt he’d be a plasma cell.

In the context of this lymph node, they’d be a sign the lymphocytes are maturing normally. But no sign exists of them here, just that big, ugly population of cells leering at me through my scope, with a few scattered small lymphocytes, red blood cells and macrophages trying to clear up the mess.

The large lymphocytes all look similar and there’s a reason – they’re the same cell. Lymphocytes have a unique rearrangement of receptors, each giving them affinity for a different antigen – this is what allows immune systems to react to the millions of different substances that can invade the body. Somewhere in the lymphatic system, there’s a lymphocyte with the substance’s name on.

Not here, though. All these lymphocytes have the same receptor; they’re clones of each other – or, at least, probably. As a pathologist, dealing with complicated and occasionally unpredictable biological systems, you quickly learn the phrase “consistent with” is your new best friend. Nevertheless, there’s going to be no “probably” about my interpretation here – large cell lymphoma.

I check the rest of the slides, but they all tell the same story, so I dictate my report into the microphone and watch it magically appear on my screen. I wipe the immersion oil from the slides, put them back in the tray and place them on the pile beside me, ready for review by one of the qualified pathologists.

…maybe not

As I lift the submission form, I notice the vet has written at the bottom: “Owner very worried.” I think about the chain of events leading to these slides being on my desk – a cuddle with a pet in front of the TV. “Can you feel those, love? Under his jaw? Are they lumps?” A telephone call. A waiting room, surrounded by other owners, worried about their pets. A consultation the owner hoped would be reassuring, but led to their vet looking concerned and taking aspirates from the lymph nodes – maybe that all happened on the same day, maybe it was booked in as a procedure. Either way, a concerned vet and some worried owners are at the other end of this submission form, waiting for results, hoping everything is going to be okay.

George walks in from the lab with another pile of forms and trays. “Urgents on top,” he calls cheerfully, and places them on top of the others, ready to be winkled.

For a moment, I look at the pile of trays and the stack of paper next to them. More than 100 sheets must be there and each piece of paper has a story behind it, just like the one I have been idly constructing for my form, whose protagonists are shortly to be informed their patient has cancer. I think of the telephone calls, treatments, stress and sadness to come that will be generated by the report I am soon to send.

I stand to pick up another submission form and tray from the pile. The excitement and interest in solving the puzzle on my slides is tempered slightly by these thoughts, but I reassure myself with the knowledge that, if I’m not giving them the answers they want, at least I’m giving them the answers they need. It’s better to know what’s going to happen than live in worry, and I recognise when I cannot help, I can explain and reassure.

As I sit back down and start to look at the next form, I think of that telephone call I had to make at the weekend. It occurs to me that maybe, in this respect at least, my new job isn’t so very different from general practice after all.

Leave a Reply