Nothing quite describes “the worst nightmare” better than having to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on our patients. Matters will only be worse if we are unprepared for it.

When I say “we”, it’s not just us veterinarians, but everyone involved, since each person’s action – or lack of action – has a direct impact on the outcome of the resuscitation.

The success of CPR is highly dependent on a few factors:

- the ability of all staff to be able to promptly identify cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) patients and commence CPR

- familiarity with compressions and ventilation protocols

- understanding the significance of monitored parameters (end tidal CO2 and ECG)

- the correct administration of emergency drugs

- preparedness for the event

In these coming blogs, I will teach you the fundamentals of CPR. Once everyone in the clinic is familiar with the procedure, everyone will be able to respond reflexively.

The power of knowledge will keep everyone calm in a stressful situation. No better team-building exercise exists than doing CPR drills regularly. Not only is it a great way to boost staff morale and build self-confidence, it is also very empowering knowing everyone can make a difference.

Part 1: be prepared

The most important aspect to resuscitation is preparation. I cannot emphasise it enough, but preparation – in both training and equipment wise – is essential to having a positive outcome.

If you have ever been in a hospital, you will notice they have fully stocked crash carts everywhere. This is not without reason. Even under ideal situations where CPR is done correctly, the overall survival rate (to discharge) continues to be low – approximately 4% to 9.6%.

This statistic is a bit more optimistic for those arrested under general anaesthetics – approximately 47%, most likely because:

- they already have venous and airway access

- the causative agent (most likely anaesthetic agents) can be removed or reversed

- the underlying disease is statistically less severe

Therefore, unless you are well prepared, you have little more than 0% success rate in CPR for your average arrested patient.

So, how can we be prepared? You can have a few things prepared beforehand that can help:

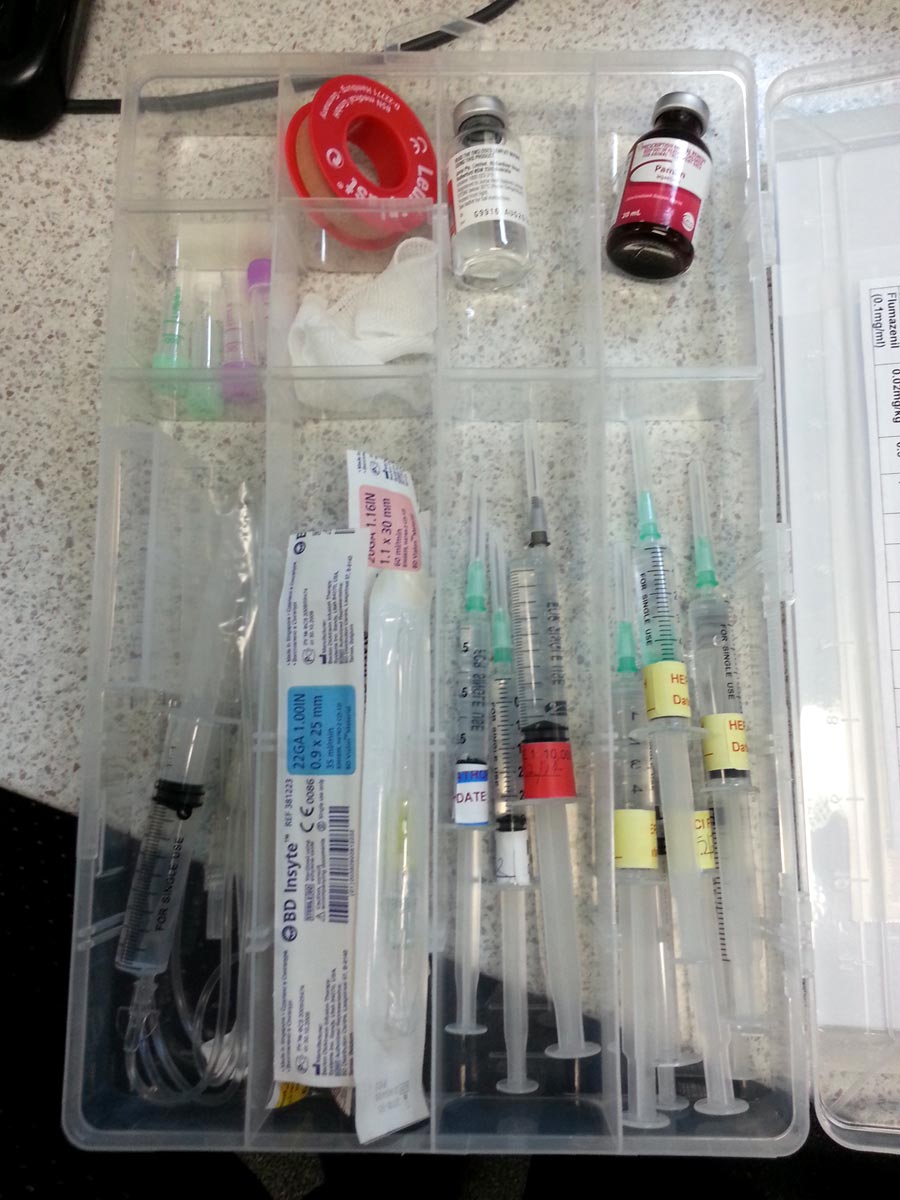

Crash kit:

- Clippers, IV catheters, IV tape, extension set, drugs, laryngoscope, endotracheal tubes and ties, flush syringes, tourniquet, CPR algorithms and dosage charts (figure 1).

- In our hospital, this crash kit is strictly used for CPR events. A seal (initial and dated) is placed across the kit’s opening to ensure this.

- An audit of the location, storage, and content of the resuscitation equipment and medications is done daily.

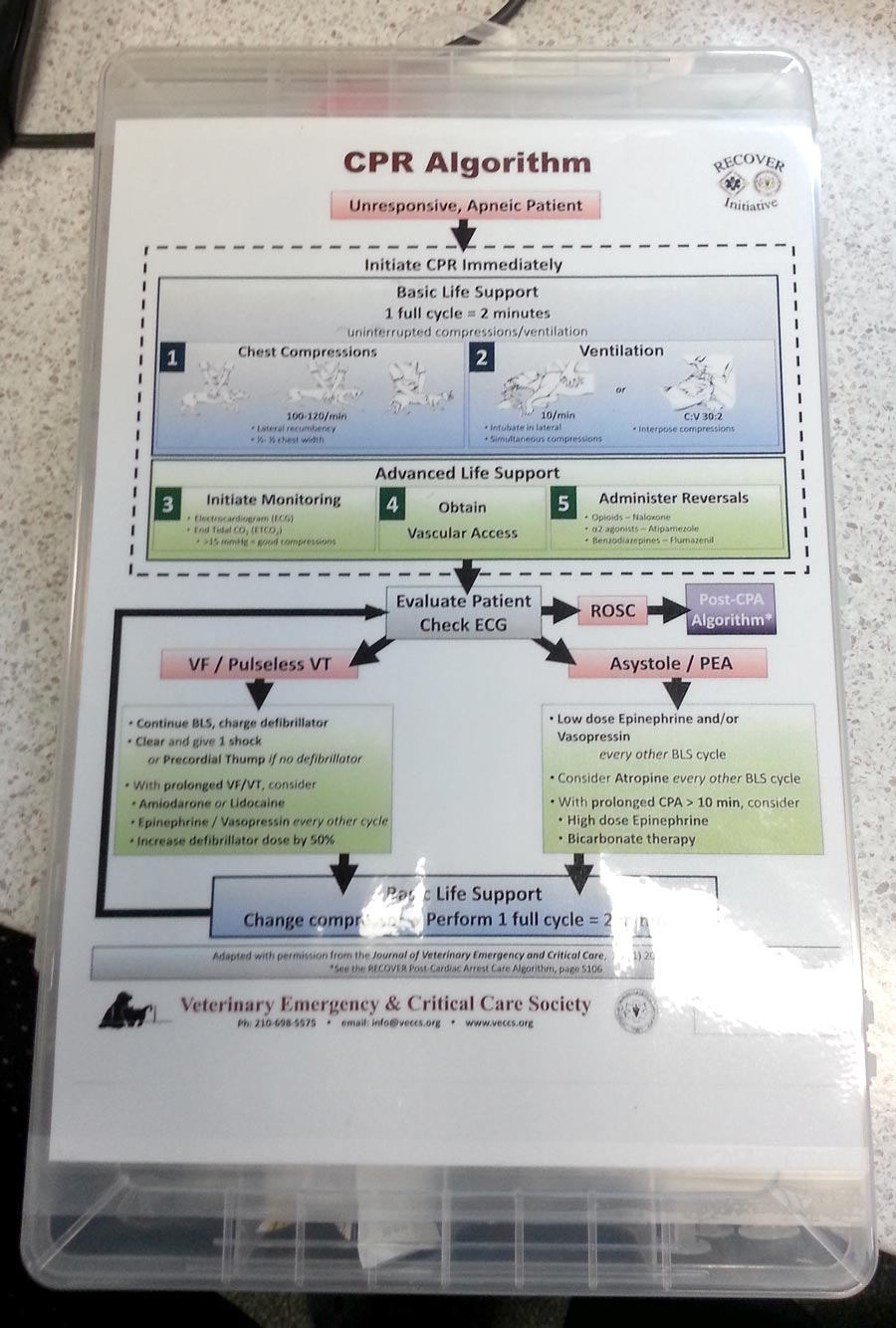

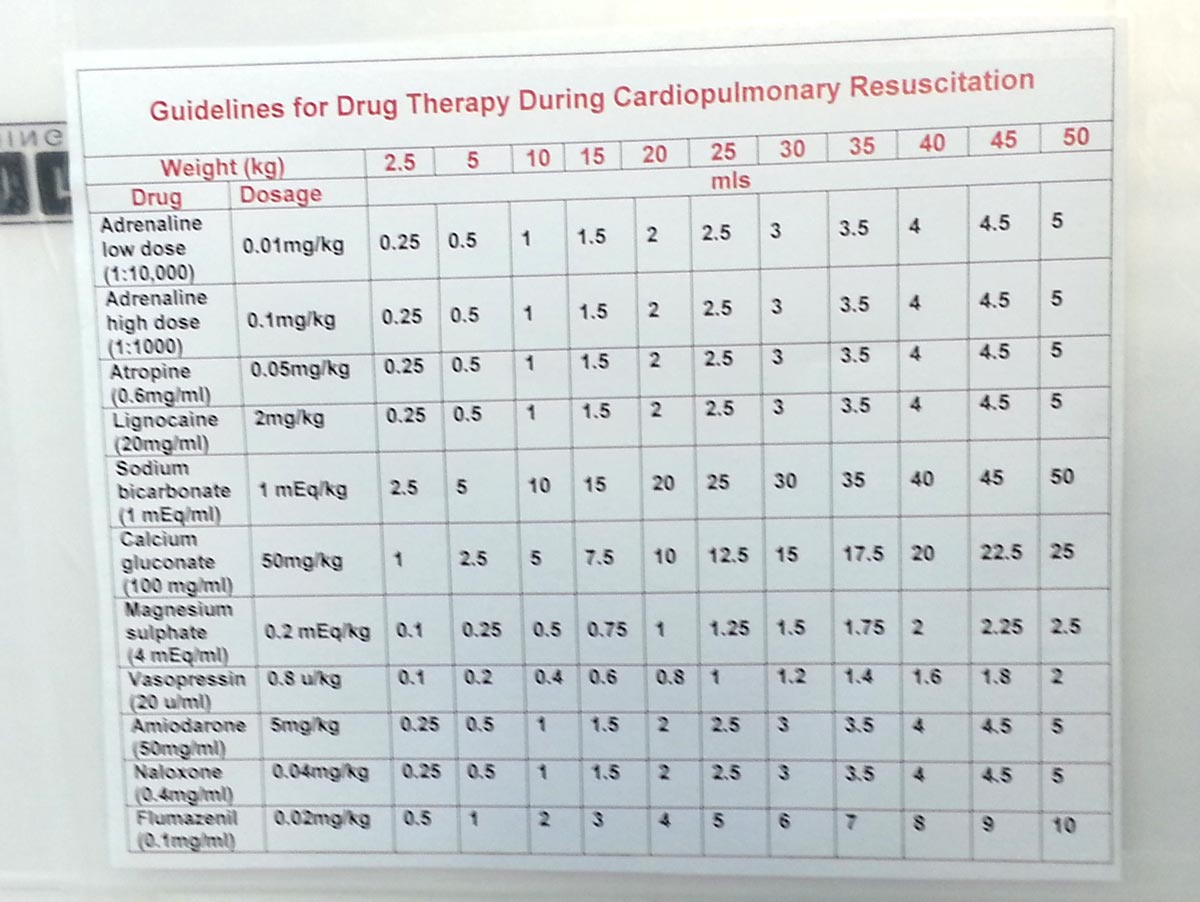

Cognitive aids:

- Standard CPR algorithms (figure 2) and dosing charts (figure 3):

- These are step-by-step prompts as to what needs to be done.

- In the event where the veterinarian is not immediately available, nurses will still be able to commence basic life support, and have other equipment and medications prepared for the veterinarian to improve response time.

CPR training:

- Refresher training needs to be done every six months for all staff members.

- Structured assessment with varied case scenarios.

Debriefing:

- Debriefing after each resuscitation effort, to review and critique the procedure, is recommended.

- Compare the actual performance to algorithms.

- This practice can significantly improve future CPR performance and efficacy.

No time to lose

In the majority of situations, the need for CPR is blindingly obvious. However, times exist when we’re not too certain and rely on the four definitive signs of CPA to make that decision. These signs are:

- loss of consciousness

- absence of spontaneous ventilation

- absence of heart sounds on auscultation

- absence of palpable pulses

While it is reasonable to have an extremely quick assessment before starting CPR (we’re talking seconds), CPR should be started immediately even if you suspect CPA has occurred. That’s right. Suspect. Unless you have witnessed CPA as it happened, the likelihood is these patients arrested some time ago. Therefore, spending a long time determining whether a pulse or heartbeat exist is counterproductive.

A lot more harm is by doing nothing. If your patient was not in CPA and you start doing compressions, the worst you can do is to wake it up. In fact, the damage you cause would be minimal and the benefit far outweighs the risks.

So, the take-home message? Just do it.

Leave a Reply