Hyponatraemia is a relatively common electrolyte disturbance encountered in critically ill patients, and the most common sodium disturbance of small animals.

In most cases, this is caused by an increased retention of free water, as opposed to the loss of sodium in excess of water.

Low serum sodium concentration

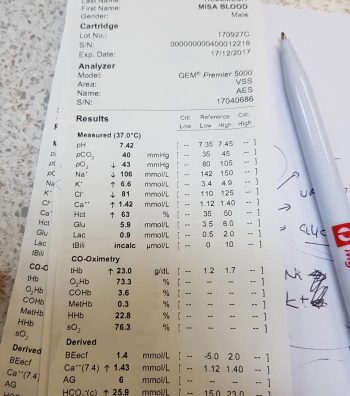

Hyponatraemia is defined as serum concentration lower than 140mEq/L in dogs and lower than 149mEq/L in cats.

The serum sodium concentration measured is not the total body sodium content, but the amount of sodium relative to the volume of water in the body. For this reason, patients with hyponatraemia can actually have decreased, increased or normal total body sodium content.

This series will look briefly at the modulators of the sodium and water balance, clinical signs associated with hyponatraemia, the most common causes in small animals, the pathophysiology behind these changes, and treatment and management.

ECF volume

Sodium is the main osmotically active particle in the extracellular fluid (ECF), so is the main determining factor of the ECF volume. Any disease process that alters the patient’s ECF volume will lead to hyponatraemia, such as:

- dehydration

- polyuria

- polydipsia

- vomiting

- diarrhoea

- cardiac diseases

- pleural or peritoneal effusion

The modulators of water and sodium balance are also different, so should be thought of as different processes.

Water balance is modulated by thirst and antidiuretic hormone, and the effect of this is to maintain normal serum osmolality and serum sodium concentration.

Modulators of sodium balance aim to maintain normal ECF volume. It adjusts this by altering the amount of renal sodium excretion; an expansion of ECF volume will lead to an increased sodium excretion, while a reduction in ECF volume will lead to increased sodium retention.

Rate and magnitude

The clinical signs of hyponatraemia are both dependent on the magnitude of the decrease and the rate at which it developed.

In mild or chronic patients, no visible clinical signs can exist. In severe (lower than 125mEq/L) and acute cases, clinical signs exhibited are typically neurological, reflecting cerebral oedema. Possibilities include:

- lethargy

- anorexia

- weakness

- incoordination

- disorientation

- seizures

- coma

Patients with acute hyponatraemia – for example, water intoxication – are more likely to show clinical signs, compared to those with chronic hyponatraemia, because the brain takes time (at least 24 to 48 hours) to produce idiogenic osmoles, osmotically active molecules that help shift free water out of brain cells.

Therefore, any acute hyponatraemia that develops within a 24 to 48-hour period tend to show clinical signs, whereas chronic cases are less likely.

- Next week’s blog will look into the different causes of hyponatraemia and how they result in sodium loss.

Leave a Reply