Systemic hypertension (SH) alone is often asymptomatic until it is severe, making early detection difficult. For this reason, it is important to know the diseases, illnesses, and other causes that can contribute to SH and recognise their clinical signs.

From there, through thorough diagnostic investigations, a diagnosis will, hopefully, result then help with the long-term management of the hypertension; as well as underlying diseases, if any.

Classification

SH can be classified as physiological, primary or secondary.

Physiological SH tends to be transient and non-sustained, often caused by the activation of the sympathetic flight or fight response from excitement, fear and/or anxiety.

With primary SH – also known as idiopathic SH – the underlying cause is unknown. This is characterised by a persistent increase in blood pressure (BP), but with normal findings on complete blood counts, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, and other diagnostic imaging and hormone tests.

Secondary SH is by far the most common form (80% of cases in dogs and cats). It can be caused by other systemic diseases, as well as certain medications.

- Systemic diseases include chronic renal insufficiency (the most common cause), acute kidney diseases, protein-losing nephropathy, hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism, hyperaldosteronism and pheochromocytomas.

- Medications known to cause an increase in BP include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, mineralocorticolids, erythropoietin, phenylpropanolamine, and sodium chloride (iatrogenic causes, as well as high-salt containing diets).

Clinical signs

Diagnosis of hypertension is relatively straight forward; however, it does rely on the clinician to have a high index of suspicion based on the history, clinical signs and physical examination findings to achieve a diagnosis. In secondary SH, the clinical signs will be associated with the underlying disease.

Three categories of clinical signs are most often observed in the hypertensive patient: ocular, cardiac and neurological.

- Ocular abnormalities are the most common clinical sign noted in hypertensive cats and dogs. These include tortuous retinal blood vessels, retinal detachment, acute blindness, hyphaema and retinal haemorrhages.

- Cats are more likely to develop cardiac abnormalities compared to dogs and typically have physical findings, such as tachycardia, heart murmurs, gallop rhythm and arrhythmias.

- Neurological signs make up only 8% of the clinical signs in a study of 200 hypertensive cats. These may present as seizure activity, a change in mentation, lethargy, head tilt, nystagmus, ataxia, hemiparesis, circling and vestibular signs.

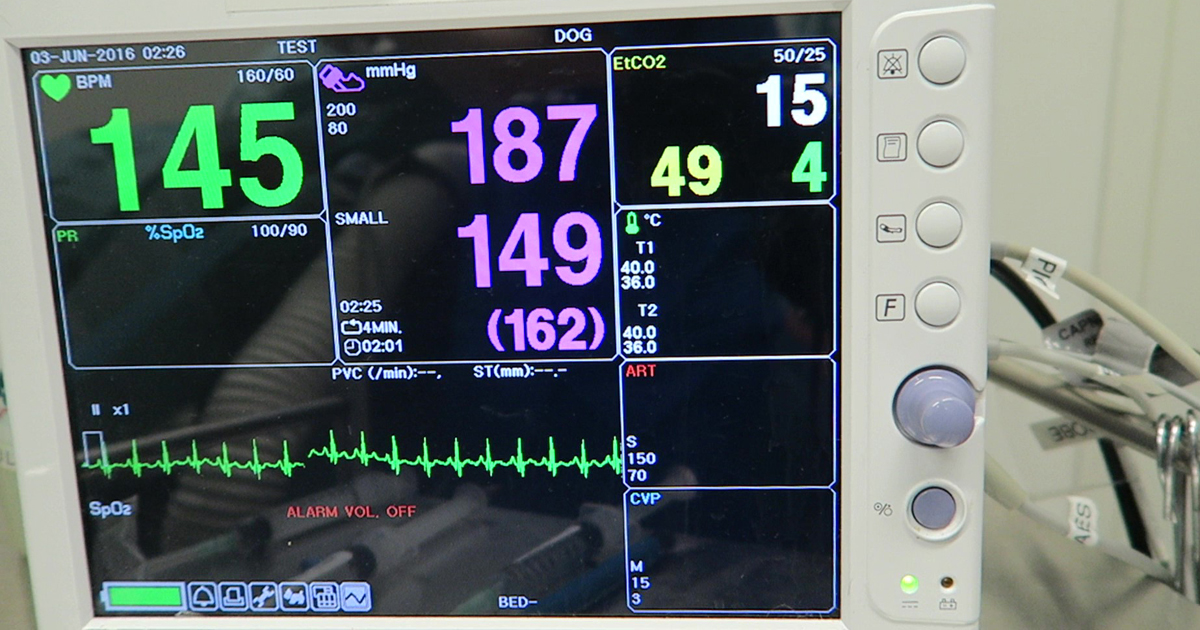

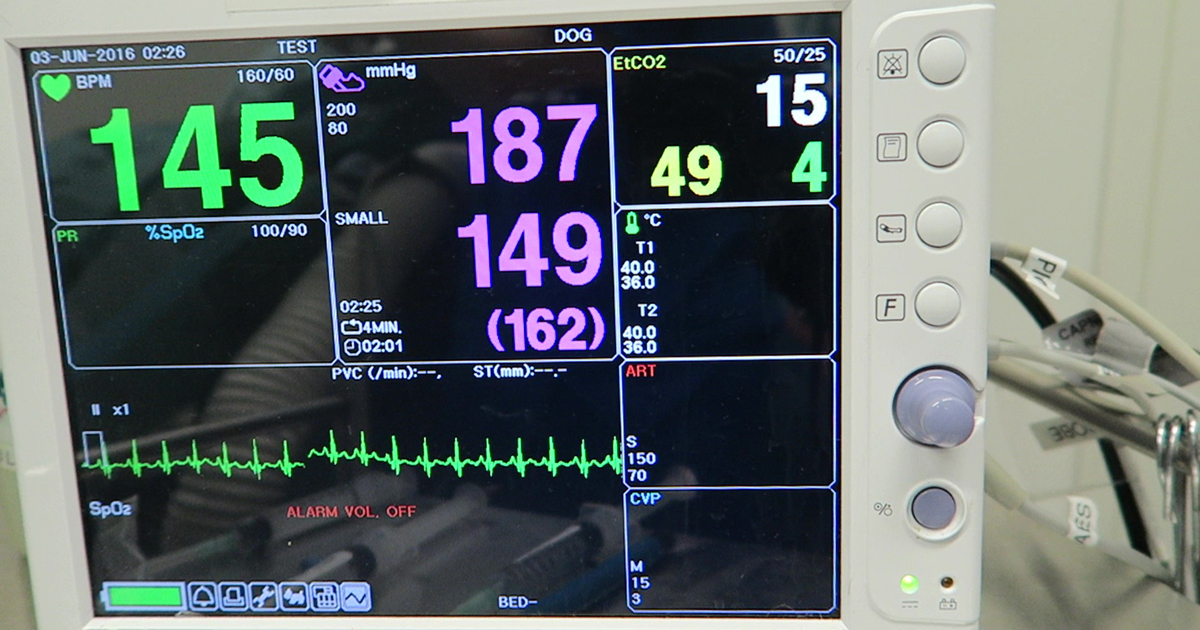

Diagnosis of SH relies on a combination of BP measurements and various laboratory tests. BP measurements can be achieved via various direct and indirect methods.

Regardless of the method used, the main thing to consider is sympathetic stress response can increase BP by approximately 20mmHg in dogs and cats. Therefore, it is essential to disregard once off, atypically high measurements, and take the average of at least three to seven subsequent measurements to get a more accurate measurement. Sometimes, hospitalisation may be required and the BP monitoring to be done over several days to accurately diagnose a persistently elevated BP.

Baseline tests

While serial BP monitoring are being done, it is important to have the baseline laboratory tests done to rule in or out underlying diseases. The minimum tests that should be performed include a complete blood count, serum biochemistry, and urinalysis.

- Complete blood counts are often normal to vague (such as anaemia of chronic disease), but can be important if an underlying disease is present.

- Serum biochemistry is extremely important in ruling out underlying disease. BUN, creatinine and phosphorus are particularly important in the case of suspected renal disease. An increased alanine transferase and alkaline phosphatase may suggest hyperadrenocorticism and hyperglycaemia may suggest diabetes mellitus.

- Urinalysis will help with confirmation of various diseases. Some abnormal findings that can be found in these patients include haematuria, glucosuria, proteinuria, increased urine protein: creatine ratio and inappropriate or decreased urine specific gravity.

- For some of these patients, based on physical examination findings and changes in the above baseline database, additional tests may be required. These may include thyroid hormone assays, ACTH stimulation test, dexamethasone suppression tests and diagnostic imaging (such as radiography, abdominal ultrasonography and echocardiography).

Diagnosis of SH is often difficult due to the absence of clinical signs during the early stages. With diligent history taking and physical examinations, SH can be diagnosed at the milder stages.

Once a diagnosis of SH has been made and all underlying disease managed, it is then vital to determine the risk of target organ damage and formulate an acute and long term management plan for SH.

Leave a Reply