Last time I talked about what happens when lymphocytes circumvent the checks and balances of the immune system, and start cloning themselves faster than Emperor Palpatine’s army.

Wanton replication with scant regard for other cells is essentially the definition of cancer – in this case lymphoma (if the cells form a solid mass in organs or lymph nodes) or leukaemia (if they fill up the bone marrow or float around in the blood).

When the normally mixed population of lymphocytes has been invaded by a single cell type, it can be a straightforward diagnosis cytologically. Can be. However, like everything in biology, it’s not always that simple.

Melting pot

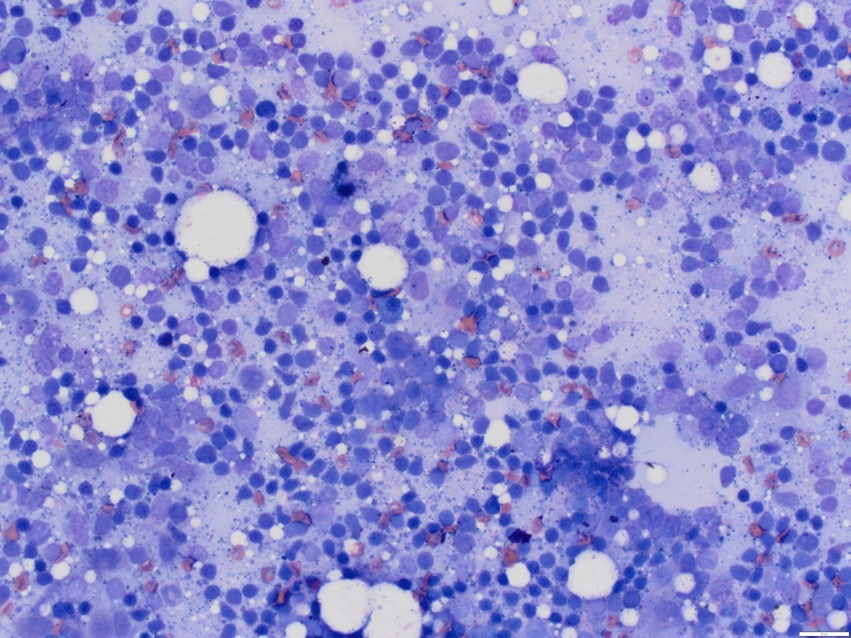

As I mentioned before, lymphocyte populations are a melting pot of small, intermediate and large lymphocytes, with a few specialised (and gorgeous) plasma cells thrown in.

Small (naive – those still searching for their own special antigen) lymphocytes should make up the bulk of this group – somewhere between 60-90% of the cells, depending upon how active the population is (although it’s very rare that we see samples from an “inactive” node because no one is likely to sample them or, honestly, be able to hit them with a needle if they try).

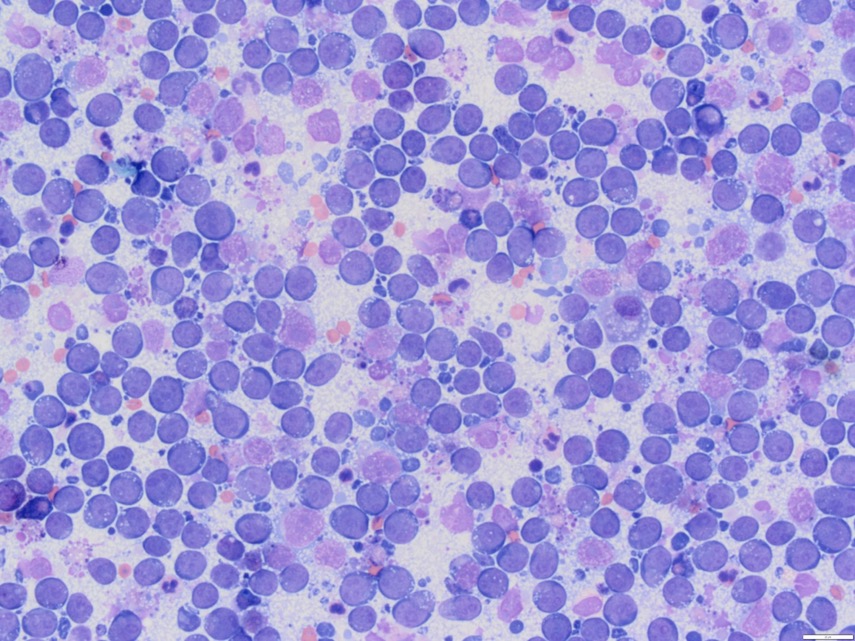

Now, when a population has been completely taken over by large lymphocytes, it looks like this instead:

In these cases, the diagnosis is straightforward, but there are many exceptions to the rule. Neoplastic (cancerous) lymphocytes are often large, blue and ugly, but not always. Small cell lymphoma is also possible and, while it is often less aggressive than large cell lymphoma (but not always), it’s very difficult to spot on cytology.

Clone clues

Look at the first picture again – there’re a lot of those small lymphocytes, and they all look pretty similar. Now, that’s how a lymph node is supposed to look, but I can’t say with absolutely confidence that all those little blue chaps aren’t all clones of the same lymphocyte.

There are often clues – there just seem to be too many small cells, and they’re often a little larger, with slightly more “open” nuclei.

Sometimes the lymphocytes have a small tapering cytoplasmic projection, and if that’s replicated in every cell you see, it’s a warning sign (traditionally, because of this projection, we call these cells “hand mirror” lymphocytes, but as we don’t all live in a Jane Austen novel, hand mirrors are in short supply nowadays and I think the terminology needs updating; if you want my opinion, they look like the score paddles that the judges hold up in Strictly Come Dancing, but I’m not sure “Strictly judge paddle cells” is going to catch on) – but these signs aren’t always present.

Uncertainty

Similarly, lymph nodes aren’t always completely overtaken by the neoplastic cells, particularly if the sample is from a node where the cells didn’t originate.

As lymph nodes become more reactive, dealing with infection and inflammation from the areas they’re draining, the intermediate and large lymphocyte numbers increase – and this is exactly what happens when a population of neoplastic lymphocytes invades. The cancer often triggers a reaction in the node, which can make the cytological pattern even more puzzling.

What I’m building myself up to say is that, even though I love my job and I’m always fascinated that we can reach a diagnosis for a patient using very cheap materials and a simple sampling technique, there are a number of times when cytologists are either unsure, or suspicious of lymphoma but can’t be certain.

That’s where further diagnostic tests come in…

Leave a Reply