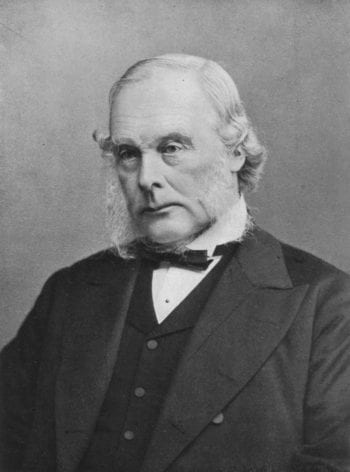

The naming of all things medical has always interested me… just who was Lister and how did he create his bandage scissors? Is there a Mr Gelpi around whose great-grandfather invented the retractors?

Surgical instruments, surgical procedures and diseases have been given a variety of weird and wonderful names over the years. However, regardless of how easy they are to remember, or how difficult they are to spell, naming things after people or places – or even species – is fraught with difficulty.

I write this partly as a vet nurse who has had to teach many of these unfamiliar names to students, and partly as a historian who is trying to unravel complex veterinary history with a limited standardised nomenclature.

Finally, I write as a Scottish expat in Kent who is seeing daily headlines about the “Kent strain“ of COVID-19. Will this have an impact on people’s willingness to visit Kent, or even travel through it, when we are allowed to leave the country again?

What’s in a name?

The World Health Organization (WHO) has noted this issue and looked at a variety of ways to try to reduce the negative impact of naming particularly diseases after people, places or even species. For example, we know now that:

- Spanish flu did not start in Spain

- bird flu is not just in birds

These names are colloquial terms that carry negative connotations, which may have a greater impact than the disease itself by inadvertently stigmatising nations, economies and people.

In more recent times the use of SARS to name an acute respiratory syndrome was contested by many in Hong Kong as its official title is Hong Kong SARS, where SARs stands for “special administrative regions”. Yet, when typing Hong Kong SARS into a search engine, the first results returned relate to death or cases of the respiratory disease.

Naming conventions

The WHO has published best practices for naming new human infectious diseases. This is so this pandemic is caused by the COVID-19 virus and not Wuhan flu. In WHO terms:

“The best practices state that a disease name should consist of generic descriptive terms, based on the symptoms that the disease causes (for example, respiratory disease, neurologic syndrome, watery diarrhoea) and more specific descriptive terms when robust information is available on how the disease manifests, who it affects, its severity or seasonality (for example, progressive, juvenile, severe, winter). If the pathogen that causes the disease is known, it should be part of the disease name (for example, coronavirus, influenza virus, Salmonella).”

Inclusive communication

So, unlike Linnaeus or Lister, new medical discoveries are unlikely to carry the name of those at the forefront of research – and the WHO would prefer that papers do not colloquialise names of diseases for the readership.

However, all this has got me thinking that, in a time where we are placing responsibility for society’s health on every person’s shoulders, surely an inclusive communication strategy is key. Is returning to a more technical naming process going to exclude those who are not comfortable using this level of language?

I don’t have any big answers, but considering how we communicate, science is an important factor – from the everyday consultation to controlling a pandemic.

Leave a Reply