Much has been written about the impact of working during COVID-19 on the mental health of nursing staff.

- Intensive therapy unit (ITU) nurses have consistently reported a range of symptoms of PTSD, having had to manage up to four or five critically ill patients who really necessitated one on one care.

- Ward nurses have struggled, as difficult decisions regarding limitations on care for patients had to be made on a daily basis.

- Senior nurses redeployed back into clinical areas after long periods in specialist roles reported stress and anxiety as they struggled to work in unfamiliar and challenging environments.

Now there is much talk of the recovery from COVID-19, nursing staff are being encouraged to reflect and rest where they can, and CPD packages on offer are focusing on inspiring and refreshing nursing teams as opposed to developing their skills and knowledge.

Recognition

Every Thursday throughout the pandemic I clapped for carers with neighbours who, knowing I was working in ITU, acknowledged my struggle; a slight raise of clapping hands and a nod in my direction told me they were thinking about me and the patients I was caring for. I remember very fondly an elderly gentleman stopping me in the supermarket when he realised I was a nurse and congratulating me on my hard work.

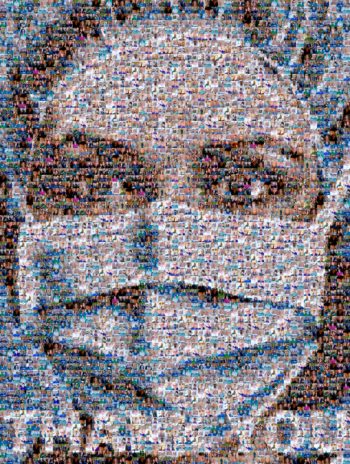

The clapping and the comments helped me, the sign painted on the roundabout that I passed on the way to work that said ‘’Thank you NHS’’ made me smile every morning.

However, as a dual qualified veterinary and human-centred nurse, my veterinary nursing colleagues are never far from my thoughts, as I knew that while I received a very public outpouring of support during the early stages of the pandemic, many of my veterinary nursing colleagues were receiving ongoing abuse and vitriol from clients.

Care less?

In a time of shifting sands and unanticipated challenges, day-to-day rules and precautions changed and, apparently, clients were angry. They ranted and raved, accusing some of my colleagues of being lazy, unorganised, difficult, or jobsworths, when all they were trying to do was care for their patients under extraordinary circumstances.

And, of course, that’s the crux of it – the mental health of all nurses takes a hit when they are unable to care for their patients in the way they feel they ought to, be they human or animal, and COVID often prevented nurses from doing just that.

As such, those nurses went home feeling guilty, tired, emotionally worn down and wishing they could have done more.

Sharing is caring

COVID-19 has focused our minds on the concept of One Health, and veterinary and medical professionals working more closely, and I am always on the lookout for opportunities for shared learning, and for promotion of a joint approach.

As a keynote speaker at Humanimal Trust’s recent One Medicine Symposium, I was reminded again how important it can be to share information between veterinary and health care professionals, potentially offering benefits to both the humans and animals involved.

Both professional groups can experience mental health problems related to their work, and I believe collaboration on a wider scale may allow nurses to care holistically, and potentially prevent some of those feelings of dissatisfaction that can impact on their mental health.

Informal referrals

I often see opportunities for collaboration in this way. Given my background, many of my human-centred nursing colleagues come to me if there is any mention of pets from their patients.

These informal referrals ranged from spending time with an elderly dementia patient who was desperately missing his Labrador and was soothed by a therapeutic sensory dog, to patients who refused to be admitted to hospital from the community as there was no one to look after their cat.

Equally, in the veterinary nursing sector, a nurse who has a strong suspicion that a pet has suffered a non-accidental injury in a household that also holds young children may struggle to know what to do. Taking that concern home, unable to offload it, may lead to sleepless nights and ongoing anxiety.

Pet bereavement is particularly relevant, and knowing a potentially vulnerable client is going home alone after their pet is euthanised can leave a veterinary nurse wondering if there is anything they can or should do to help.

Collaboration

Not every human patient will come with animal-related issues and not every veterinary client will need further support. Nevertheless, when they do, wouldn’t it be wonderful if human-centred and veterinary nurses could share resources, refer cases and care holistically? If they could, surely they are far more likely to leave work with a clear head, knowing they have been able to manage something integral to the health and well-being of their patient.

There are many fantastic examples of co-operation between services. I recently learned of a practice that formed a collaboration with their local branch of Samaritans, so they have the capacity to refer any vulnerable bereaved clients to them.

Foster carers for the pets of those people fleeing domestic violence, the upcoming concept of using veterinary social workers in practice – there are so many incredible projects, but surely it’s time for a much broader approach? Can we think of one? Do we need to educate our nurses together?

Start a conversation

How can we develop a professional forum where a human-centred nurse may access information about pet bereavement? Or a veterinary nurse may signpost a client to smoking cessation services with the aim of improving the quality of life of the terrier that shares the cigarette smoke?

While the internet is full of resources, crucially it is about having the confidence to start a conversation; remaining within a specific scope of practice, but perhaps, thinking a little more laterally. Taking the time to pick up the phone or write an email to a specialist hospital nurse, a local veterinary practice or health care agency.

To borrow a phrase recently used by the Duchess of Cambridge for an equally ambitious project: “Big change starts small”. Perhaps taking a chance and writing that email, or taking that phone call, can be the small change that moves collaboration forward in a meaningful way?

Leave a Reply